Early last month, just weeks before the election, the husband of one of the candidates for president of the Philippines renounced his U.S. citizenship. As Rappler reported:

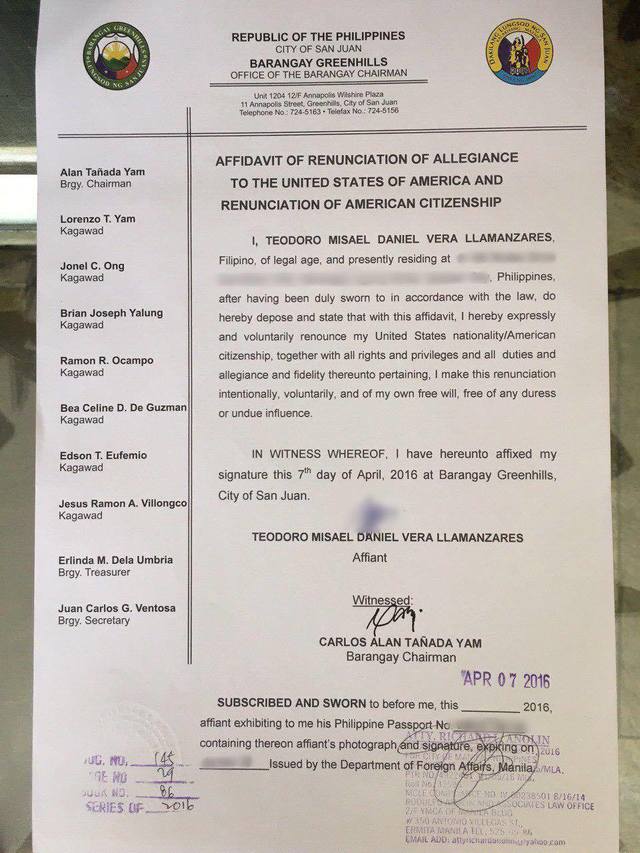

Teodoro Misael Daniel “Neil” Vera Llamanzares filed his renunciation of his US citizenship on Thursday, April 7, before Carlos Alan Tañada Yam, chairman of Barangay Greenhills in San Juan.

Llamanzares signed 2 documents: the Affidavit of Renunciation of Allegiance to the United States of America/Renunciation of American Citizenship and his Oath of Allegiance to the Philippines.

Llamanzares, in his affidavit, said “I…expressly and voluntarily renounce my United States nationality/American citizenship, together with all rights and privileges and all duties and allegiance.”

It would be interesting to know if Philippine banks would accept a certificate like the one pictured above as proof that one was not a “U.S. person”, but it looks like we’re not going to find out in this case: Llamanzares already went and paid the U.S. Embassy in Manila’s extortionate fee to obtain one of their CLNs as well.

Also, since Llamanzares is a Very Important Person and not just one of us tax-evading money-laundering drug-dealing America-hating terrorist bloggers, they gave him one of those rare, strictly-rationed appointment slots and processed his paperwork in record time — the same high level of service that Fauzia Kasuri of Pakistan enjoyed a few years ago back when the fee was less than a fifth of its present level. A few days before the election, the Philippine Inquirer revealed:

Senator Grace Poe said her husband Neil Llamanzares has completed his renunciation of his US citizenship and is expected to receive Friday a certification from the US embassy.

“I’d to clarify this issue once and for all, my husband has renounced before a public officer here in the Philippines and has done so also in the US embassy and he’s actually getting his certificate already today,” Poe said in an interview over ABS-CBN News Channel’s (ANC) Headstart program.

Unfortunately for Ms. Poe, she lost the election, but look on the bright side: at least she and her husband are both now free of any peeping foreign perverts invading the privacy of their marriage.

Oath of allegiance to a foreign state

In the U.S., the Expatriation Act of 1868 affirmed that “the right of expatriation is a natural and inherent right of all people”, and in the debate leading up to its passage, Senator Edwin D. Morgan (R-NY) pointed out that requiring a person to apply for proof from his former government that he’d renounced its citizenship was tantamount to admitting that renunciation was a privilege requiring permission for the exercise, rather than a natural and inherent right. Philippine statutes apparently also recognise this idea, though I can’t cite verse & chapter — I’m just relying on Rappler‘s description:

Under Philippine law, a person only needs to take an oath of renunciation of foreign nationality before a notary public to effectively reject it.

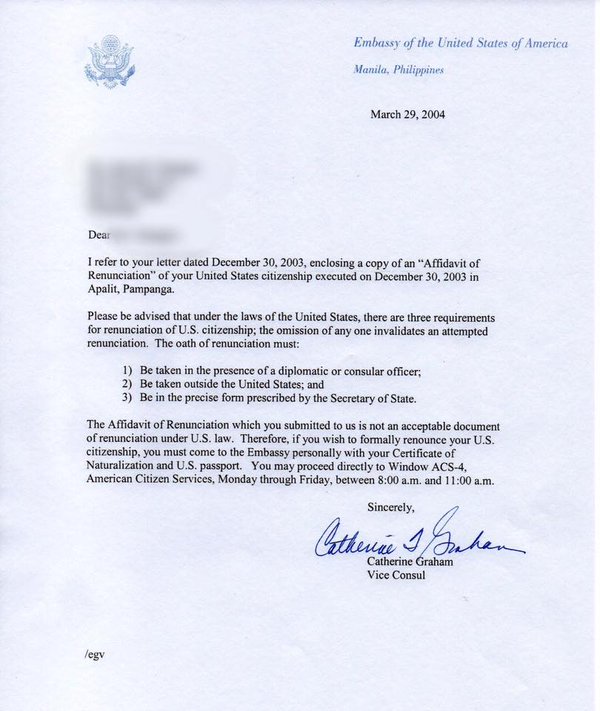

But under US law, one has to fill out a questionnaire at the US embassy to confirm the renunciation. After which, the consular officer would issue a Certificate of Loss of Nationality.

Poe said her husband has already started the renunciation process before the US government but it would likely take a long time, just like her experience.

However, U.S. State Department officials clearly don’t share Morgan’s attitude, as seen in this response of theirs to another Filipino who tried to exercise his rights under both the Expatriation Act of 1868 and the laws of his own country to divest himself of foreign allegiances:

Even if the apparently-not-very-well-informed Ms. Graham had been aware that an oath of allegiance to a foreign state is an expatriating act under 8 USC § 1481(a)(2), her department has already made their best efforts to ignore Congress and make that provision of law into a dead letter by adding all sorts of nonsensical requirements which appear nowhere in the statute nor in the court case they cite in support of their position. 7 FAM 1252:

h. For an oath or affirmation to be potentially expatriating, it must be meaningful. A meaningful oath is one that is required by a foreign state. Such an oath reflects a transfer of allegiance to a foreign state and/or the abandonment of allegiance to the United States. Gillars v. United States, 182 F.2d 962 (DC 1950). An oath or affirmation will be found to be meaningful only if all four of the following criteria are met:

(1) The oath or affirmation is made to an official of a foreign state authorized to receive the oath or affirmation;

(2) The authorized foreign official in fact does receive the oath or affirmation;

(3) The oath or affirmation is made in a manner that is consistent with the foreign state’s law; and

(4) The making and receipt of the oath or affirmation alters the affiant’s legal status with respect to the foreign state.NOTE: For example, a person who has already acquired a foreign nationality may not expatriate herself by swearing an oath of allegiance to that same foreign state because she already owed that state her allegiance, unless the foreign state’s law specifically grants her a new right after making the affirmation not already conferred upon by virtue of her prior naturalization.

The Department determines on a case-by-case basis whether an oath of allegiance is meaningful for purposes of INA 349(a)(2).

What the DC Circuit Court actually noted in Gillars was that the paper that Gillars’ German boss made her sign after her little workplace spat was so vague and informal that it didn’t meet the bar of “to a foreign state”. The court made no mention whatsoever of the oath needing to confer new rights on or otherwise alter the legal status of the affiant:

There is no indication, however, that the paper which she said she signed was intended as a renunciation of citizenship; there is no testimony whatever that it was sworn to before anyone authorized to administer an oath or indeed before anyone at all; its exact content is uncertain; if it be treated as an affirmation or declaration rather than an oath it is informal rather than formal in character; and there is no connection whatever shown between it and any regulation or procedure having to do with citizenship or attaching oneself to the Reich or to Hitler. These circumstances preclude attributing to it the character of such an oath or affirmation or other formal declaration as the statute requires to bring about expatriation. We think the court was correct in not permitting the jury to speculate as to the effect of this testimony on citizenship and in ruling that as a matter of law the appellant at the times involved was a citizen of the United States and owed allegiance to her native land.

However, the paper that Llamanzares signed has none of the defects mentioned in Gillars: it contains language expressly renouncing foreign citizenship, he clearly signed it with the intent of divesting himself of foreign citizenship, and he signed it in the presence of officials of his govenrment authorised by their domestic statutes to administer such oaths.

FATCA IGAs & altering your legal status

And furthermore, even if you adhere to the State Department’s extralegal, ultra vires viewpoint on oaths of allegiance, there’s good news. FATCA Inter-Governmental Agreements create two classes of citizenship in every signatory country: those local citizens who are deemed U.S. persons and thus must forfeit their privacy rights so that the banks don’t get an extra 30% of their U.S.-source income stolen by the IRS, and those local citizens who are not deemed U.S. persons and thus get to keep their privacy rights. To swear an oath which moves you from one category to the other is obviously an “alter[ation] of the affiant’s legal status”.

As Isaac Brock Society commenter George has long suggested: every government on Earth should give their citizens an inexpensive and practical way to swear an oath to renounce all foreign citizenships, and should issue certificates to those who have done so. Call it a “Certificate of Loss of Nationality of [INSERT FOREIGN COUNTRY HERE]”. Thus they could issue Certificates of Loss of Nationality of the Islamic Republic of Iran to Iranians (turning them into ex-Iranians), Certificates of Loss of Nationality of the Republic of Korea to South Koreans (turning them into ex-South Koreans), and Certificates of Loss of Nationality of the United States of America to Americans (turning them into ex-Americans).

A person holding such a certificate should have the right to be treated solely as a citizen of his or her country by all public and private institutions, and the duty to conduct him or herself as such (for example, not using a foreign passport to travel to other countries, and not voting in foreign elections). This may require additional legislation, as it’s not an automatic consequence of the Master Nationality Rule (which only binds governments, not banks and their maximalist-extremist lawyers acting under fear of IRS penalties or DOJ investigations).

So in particular, your local government must pass legislation to ensure that banks accept these certificates as proof of non-U.S. personhood for FATCA purposes. Under the IGA, bank customers with U.S. indicia are required to provide a “reasonable explanation” of not having a U.S.-issued CLN; well, the obvious one is that the U.S. State & Treasury Departments have made such CLNs unreasonably time-consuming, expensive, and dangerous for ordinary people to obtain.

But as long as domestic legislation states that the holding of a domestic-law Certificate of Loss of Nationality of [BLANK] qualifies under the IGA as a “reasonable explanation” or even as a “Certificate of Loss of Nationality of the United States” (a term which is not expressly defined in any IGA I’ve seen), then anyone who swears the oath to obtain such a certificate has had their legal status altered by swearing the oath. Problem solved!

Conclusion

As certain Members of Parliament in Canada like to say: Congress has spoken! In fact they’ve spoken quite clearly, for nearly 150 years, with the Expatriation Act of 1868, and now it’s up to every other country in the world to jump up and implement it in their domestic laws, the same way they jumped to implement FATCA. Get moving!

@Norman Diamond: Some do, most don’t, and most aren’t by force. Meanwhile, I know some Filipinos who visit the Philippines, and some Canadians who visit Canada

If you can’t visit the Philippines, or Canada for whatever reason, you can call or write or send an email, or if you all have the money you can meet in another country. Relatives of North Koreans face well-known restrictions on those options.

Sure, you’re not forced to keep in touch with your relatives. And you’re not forced to earn income above the US reporting threshold either. (Your local laws may force you to maintain “foreign” structures which have US reporting requirements, but no one forced you to move to such a country in the first place.)

Lots of countries’ diasporas send money to relatives so the relatives don’t starve to death. One of many many examples would be, by the way, ahem, the Philippines. … Anyway these aren’t taxes.

When the government takes a portion of the remittance (whether directly, or through non-market exchange rates), then indeed that’s a tax. Not a citizenship-based tax, of course, since among other things you can’t get out of it by renouncing citizenship, but “diaspora taxation” does not always mean the same thing as “citizenship-based taxation”.

Incidentally, the Philippines used to tax remittances — 15 bps “Documentary Stamp Tax” on inbound money transfers — but remittances by overseas Filipino workers are exempt from this since a few years ago. Last I read, Cuba has some sort of remittance tax, but this might have changed.

Is this because the North Korean government knows who their relatives are and where their relatives live? If not, what kinds of actions are taken to get payments by force instead of persuasion?

I don’t know exactly. I think the people who have been interviewed for books and newspapers on this topic are describing things truthfully, even if they’re not especially concrete. Random examples:

http://apjjf.org/-John-Feffer/2327/article.html

https://www.dailynk.com/english/read.php?cataId=nk00100&num=7216

The interesting aspect of the Philippines affidavit of renunciation of allegiance to any foreign prince, potentate, state, or sovereignty (to borrow a phrase from the US naturalization oath) is that if — as presumably in the case of the naturalization oath, at least in the past — this would mean that the Philippines will treat the renunciant as no longer a US Person whatever the USG may say and that the renunciation is effective under Philippine law and overrides any contrary US law or US-Philippine treaty (tax treaty, IGA) to the contrary. At least insofar as cross-border enforcement is concerned.

In any case it remains to be seen whether it will be true that many or most countries will accept a vague definition of US citizen for tax purposes. It may be true that international law gives each country sole authority to determine who are its citizens, but that is not the whole story. Exorbitant attribution of citizenship need not be recognized by other countries, and often the State Department does not: it does warn its citizens traveling abroad of the risks, such as military service or prosecution for treason and limitation on consular “protection”. (An acquaintance of Lebanese descent was warned in the 1970s that as his name appeared to be typically Greek he should be cautious in visiting Greece as many Greek-Americans had been conscripted into military service in the past. Some of these cases were intentional, to avoid US conscription and service in Vietnam, but that’s another story.)

Current treaties with mutual collection provisions (Canada, Denmark, France, Netherlands, Sweden) exclude persons who were citizens of the requested country at the time the taxes were incurred. This could create an anomaly with certain countries (EU/EEA/Switzerland; British Common Travel Area (Ireland Act 1949: Irish citizens are not “aliens” in Britain). Unilateral renunciation creates another anomaly.

Philippine CBT was a relic of US taxation law incorporated into Philippine domestic law in 1913. It became untenable when devaluation of the peso put even low-paid Filipino expat workers into a high tax bracket. For background see Richard D. Pomp, The Experience of the Philippines in Taxing Its Nonresident Citizens, 17 N.Y.U. J. Int’l L. & Pol. 245 (1985) http://uniset.ca/art/17NYUJILP245.pdf (article pre-dates the change to RBT). The National Internal Revenue Code of 1997 is here: http://www.chanrobles.com/legal6nationalinternalrevenuecodeof1997.html#.V0lGfmOe2FU

http://www.smh.com.au/queensland/dual-citizenship-concerns-forget-the-high-court-a-brisbane-bookshop-can-ease-your-troubles-20171006-p4ywb8.html

Botswana appears to be doing something similar: letting people with an uncertain claim to foreign citizenship renounce that claim by filing paperwork with Botswana’s government instead of trying to get documents from the foreign government.

http://www.weekendpost.co.bw/wp-news-details.php?nid=5388 (archived https://archive.fo/6Wp6e)

Although the people concerned by the Botswana decision are extremely unlikely to include US citizens, it would be theoretically interesting to see if banks in Botswana accepted this renunciation from someone with a US birthplace, for instance, and not consider that person a USP.

Does it mean that a Botswana-US dual citizen who is at risk of losing their Botswana citizenship if they don’t renounce the US citizenship, can be treated as not having the US citizenship and allowed to resume Botswana-only citizenship?

Or have I misunderstood?

If that’s what it means, and it lets the person not be treated as FATCA-reportable, it seems like an excellent solution.

What IGA does Botswana have?

Botswana appears to be following a different drummer:

http://www.weekendpost.co.bw/wp-news-details.php?nid=5398

It brings home the fact that for dual USCs in most countries, it’s not their US-Personhood that’s the problem, it’s their bank’s.