As previously discussed by Petros and Innocente, countries including Germany, Austria, and Norway, which generally require applicants for naturalisation to give up foreign citizenship, provide for an exception if the old country makes giving up citizenship especially difficult. Some countries’ definitions of “difficult” include economic difficulties, such as a fee which is more than a certain proportion of the applicant’s monthly wage. In 2014, the United States announced that it was raising the fee for renunciation to $2,350, twenty times the average level of other developed countries, more than twice the level charged by the next-highest country I could find (Jamaica), and greater than the monthly wage for many young people or non-professionals.

As previously discussed by Petros and Innocente, countries including Germany, Austria, and Norway, which generally require applicants for naturalisation to give up foreign citizenship, provide for an exception if the old country makes giving up citizenship especially difficult. Some countries’ definitions of “difficult” include economic difficulties, such as a fee which is more than a certain proportion of the applicant’s monthly wage. In 2014, the United States announced that it was raising the fee for renunciation to $2,350, twenty times the average level of other developed countries, more than twice the level charged by the next-highest country I could find (Jamaica), and greater than the monthly wage for many young people or non-professionals.

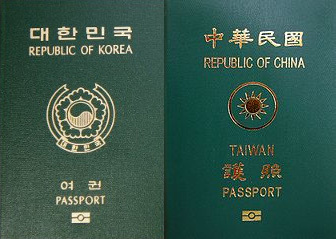

South Korea’s Nationality Act also contains such a “difficulty” exception, while Taiwan has a similar exception for “reasons not attributable to the person in question”. However, neither definition includes absurd fees such as Washington’s $2,350 fee — which is more than seventy-eight times Taipei’s fee and one-hundred-and-seventeen times Seoul’s fee for their own citizens seeking to exercise their fundamental human right to change their nationality.

South Korea at least allows successful applicants one year after the event of naturalisation to submit proof of loss of their previous citizenship, meaning that American emigrants there can relinquish rather than renounce U.S. citizenship and avoid the fee. Taiwan, in contrast, requires such proof to be submitted at the time of application; though recently there have been proposals to change this, until those proposals become law, American emigrants seeking to become citizens there still have to pay through the nose to renounce U.S. citizenship rather than relinquish it.

Table of contents

- South Korea: no statutory definition of “difficulty”

- Regulations define “difficulty” narrowly

- Taiwan: current law

- “Preliminary proof” insufficient for U.S. relinquishment

- Proposed reform

South Korea: no statutory definition of “difficulty”

Unlike Taiwan’s laws, South Korea’s Nationality Act excepts certain immigrants & returnees from the general principle of single nationality. Most applicants for naturalisation or restoration of citizenship must present proof from their other country of having gone through the procedures under that country’s law to give up that citizenship. However, people from mixed-nationality families, the elderly, those who have made special contributions to the country, and those who have difficulty giving up foreign citizenship can all avoid those procedures, as long as they swear an oath not to “exercise” their foreign nationality while in South Korea.

That oath is, basically, a domestic-law implementation of the Master Nationality Rule. Note, however, that it only prohibits individual South Korean citizens or the other government which claims them from asserting rights which arise from that foreign nationality against the South Korean government when the person is in South Korea. The oath, and the Rule in general, does not prohibit any government or private actors from using the fact that a person might be considered a national of some other country under that country’s law to discriminate against that person. Protecting people against such discrimination actually requires anti-discrimination laws, not just the Master Nationality Rule.

제10조(국적 취득자의 외국 국적 포기 의무) |

Article 10 (Duty of person acquiring nationality to abandon nationality of foreign country) |

| ① 대한민국 국적을 취득한 외국인으로서 외국 국적을 가지고 있는 자는 대한민국 국적을 취득한 날부터 1년 내에 그 외국 국적을 포기하여야 한다. | (1) A person who, being a foreigner, acquires the nationality of the Republic of Korea and holds the nationality of a foreign country shall, within one year from the day of acquiring the nationality of the Republic of Korea, abandon the nationality of the foreign country. |

| ② 제1항에도 불구하고 다음 각 호의 어느 하나에 해당하는 자는 대한민국 국적을 취득한 날부터 1년 내에 외국 국적을 포기하거나 법무부장관이 정하는 바에 따라 대한민국에서 외국 국적을 행사하지 아니하겠다는 뜻을 법무부장관에게 서약하여야 한다. | (2) Paragraph 1 notwithstanding, a person to whom one of the following subparagraphs is applicable shall, within one year from the day of acquiring the nationality of the Republic of Korea, abandon the nationality of the foreign country or, in the manner prescribed by the Minister of Justice, make an oath to the Minister of Justice of his intention not to exercise the nationality of a foreign country within the Republic of Korea. |

| 1. 귀화허가를 받은 때에 제6조제2항제1호·제2호 또는 제7조제1항제2호·제3호의 어느 하나에 해당하는 사유가 있는 자 | 1. A person to whom is applicable any one of the grounds of Article 6, Paragraph 2, Subparagraph 1 or Subparagraph 2, or Article 7, Paragraph 1, Subparagraph 2 or 3 at the time he receives permission for naturalisation |

| 2. 제9조에 따라 국적회복허가를 받은 자로서 제7조제1항제2호 또는 제3호에 해당한다고 법무부장관이 인정하는 자 | 2. A person who received permission for restoration of nationality according to Article 9 and is confirmed by the Minister of Justice as a person to whom Article 7, Paragraph 1, Subparagraph 2 or Subparagraph 3 is applicable |

| 3. 대한민국의 「민법」상 성년이 되기 전에 외국인에게 입양된 후 외국 국적을 취득하고 외국에서 계속 거주하다가 제9조에 따라 국적회복허가를 받은 자 | 3. A person who, prior to becoming an adult under the Civil Code of the Republic of Korea, was adopted by a foreigner and later acquired the nationality of a foreign country and continued to reside in a foreign country, and receives permission for restoration of nationality under Article 9 |

| 4. 외국에서 거주하다가 영주할 목적으로 만 65세 이후에 입국하여 제9조에 따라 국적회복허가를 받은 자 | 4. A person who resided in a foreign country but, after reaching the age of 65, enters the country and receives permission for restoration of nationality under Article 9 |

| 5. 본인의 뜻에도 불구하고 외국의 법률 및 제도로 인하여 제1항을 이행하기 어려운 자로서 대통령령으로 정하는 자 | 5. A person who is confirmed by the Minister of Justice as having difficulty in fulfilling the provisions of Paragraph 1 arising from the law or system of the foreign country despite the person’s own intention, as defined by presidential order |

| ③ 제1항 또는 제2항을 이행하지 아니한 자는 그 기간이 지난 때에 대한민국 국적을 상실한다. | (3) A person who does not fulfill Paragraph 1 or Paragraph 2 shall, upon the passage of that period of time, lose the nationality of the Republic of Korea. |

One small mercy is that Article 10 of the Nationality Act only requires you to give up your foreign citizenship after you have been naturalised; thus, Americans can treat their acquisition of South Korean citizenship as a relinquishing act under 8 USC § 1481(a)(1), and report it to the U.S. consulate as such in order to avoid the absurd renunciation fee.

Regulations define “difficulty” narrowly

As you can see in Subparagraph 5 above, the National Assembly chose to let the executive decide exactly what constitutes “difficulty … arising from the law or system of the foreign country despite the person’s own intention”. The statute might give the executive the authority to decide that absurd renunciation fees or other economic difficulties constitute “difficulty”, but the executive has decided not to exercise that authority, for now: current regulations define “difficulty” narrowly. The only people exempt from the duty of abandoning their foreign citizenship under the foreign country’s laws are those for whom such abandonment is impossible. Those who face extreme delay are exempted for only so long as it takes them to complete the procedure.

시행령제13조(외국 국적 포기가 어려운 자 등) |

Implementation Order, Article 13 (Person for whom it is difficult to abandon the nationality of a foreign country, etc.) |

| ① 법 제10조제2항제5호에서 “대통령령으로 정하는 자”란 다음 각 호의 어느 하나에 해당하는 사람을 말한다. | (1) In Article 10, Paragraph 2, Subparagraph 5 of the Act, “a person … defined by presidential order” means a person to whom one of the following subparagraphs is applicable. |

| 1. 외국의 법률 및 제도로 인하여 외국 국적의 포기가 불가능하거나 그에 준하는 사정이 인정되는 사람 | 1. A person for whom it is confirmed it is impossible to abandon the nationality of a foreign country due to reasons arising from the law or system of the foreign country, or circumstances equivalent to that |

| 2. 대한민국 국적을 취득한 후 지체 없이 외국 국적의 포기절차를 개시하였으나 외국의 법률 및 제도로 인하여 법 제10조제1항에 따른 기간 내에 국적포기절차를 마치기 어려운 사정을 증명하는 서류를 법무부장관에게 제출한 사람 | 2. A person who, after acquiring the nationality of the Republic of Korea, commenced the procedure for abandoning the nationality of the foreign country without delay, and submits to the Minister of Justice documents proving difficult circumstances in the procedures for abandoning the nationality of the foreign country within the period under Article 10, Paragraph 1 of the Act for reasons arising from the law or system of the foreign country |

| ② 제1항제2호에 해당하는 사람이 외국 국적의 포기절차를 마쳤을 때에는 지체 없이 국적포기증명서등을 법무부장관에게 제출하여야 한다. | (2) A person to whom Paragraph 1, Subparagraph 2 is applicable shall, upon completing the procedures for abandonment of nationality of the foreign country, submit the certificate of abandonment of nationality, etc. to the Minister of Justice without delay. |

Taiwan: current law

Under Taiwan’s current Nationality Law, immigrants applying for naturalisation must give up their former citizenships, while emigrants from Taiwan who apply for another citizenship are allowed to retain their Republic of China citizenship. This is similar to the situation in Estonia, Namibia, and Hong Kong — all of those being places which were formerly under foreign control, and in which the new governments wanted to disallow colonists from the former colonial metropole or occupying power to become dual citizens, but ended up allowing their diasporae to retain citizenship.

However, Taiwan in particular has a very strange requirement: you must make yourself stateless before you apply for naturalisation, and submit a certificate of loss of your original nationality along with your application, without any guarantee that your application will be approved. In practice, there’s procedures for pre-application screening, but even after the official application has been submitted, the government can still reject it. In some cases this makes it impossible for people to apply for naturalisation at all; in others it’s left them stateless after their applications were turned down, for example if an applicant applies for accelerated naturalisation on the basis of marriage but the marriage ends due to divorce or death while the application is still pending.

第九條 |

Article 9 |

| 外國人依第三條至第七條申請歸化者,應提出喪失其原有國籍之證明。但能提出因非可歸責當事人事由,致無法取得該證明並經外交機關查證屬實者,不在此限。 | A foreigner who applies for naturalisation under Article 3 through Article 7 shall submit proof of loss of his original nationality. However, for a person who submits that reasons not attributable to the person in question make it impossible to obtain proof of loss of the original nationality, upon inspection and verification by the foreign affairs organs, this limitation shall not apply. |

Current regulations don’t define “reasons not attributable to the person in question”, but in administrative practice this apparently is interpreted to mean either that the country in question doesn’t allow loss of nationality at all, or won’t let its loss-of-nationality provisions be triggered by naturalisation in Taiwan because the country doesn’t recognise Taiwan’s government. Difficulty in renouncing citizenship (e.g. due to absurd fees or extreme delays) doesn’t trigger this provision either.

“Preliminary proof” insufficient for U.S. relinquishment

Current regulations do state that the Ministry of the Interior will issue “preliminary proof of naturalisation to the nationality of the Republic of China” to naturalisation applicants. This is one possible attempt at a literal translation of the Chinese name (準歸化中華民國國籍證明); the Ministry of the Interior officially calls the document they issue under these regulations a “Certificate of ROC Naturalization Candidacy”.

In any case, the Chinese name (particularly the character “準”) & its English translation are sufficiently vague that the ministry felt obliged to clarify in the regulations that this certificate is not actual naturalisation which could later be cancelled, and doesn’t come with any of the privileges of nationality; nor is it even a guarantee that naturalisation will be granted after the applicant gives up foreign citizenships. In my below translation, I’ve used the “preliminary proof of naturalisation” rather than the official name.

施行細則第十條 |

Implementation Rules, Article 10 |

| 外國人為依本法第九條規定提出喪失其原有國籍證明,得填具準歸化國籍申請書,並檢附第八條第一項第二款至第八款或前條第一款、第三款所定文件,向國內住所地戶政事務所申請準歸化中華民國國籍證明,由該戶政事務所查明其刑事案件紀錄,併送直轄市或縣(市)政府轉內政部核發。 | A foreigner, in order to obtain proof of loss of the original nationality under Article 9 of the Law, may complete an application form for preliminary naturalisation, including for inspection the documents specified in Article 8, Paragraph 1, Subparagraph 2 through Subparagraph 8 or Subparagraph 1 and Subparagraph 3 of the preceding article, and submit it to the household registration office in his place of domicile in order to apply for preliminary proof of naturalisation to the nationality of the Republic of China. That household registration office shall ascertain [the applicant’s] criminal record, and then send [the documents] to the government of the special municipality or county (city) for forwarding to the Ministry of the Interior. |

| 前項所定準歸化中華民國國籍證明之有效期限為二年,僅供外國人持憑向其原屬國申辦喪失原有國籍,不作為已歸化我國國籍之證明。 | The validity period of preliminary proof of naturalisation to the nationality of the Republic of China under the preceding paragraph is limited to two years. It is provided only so that a foreigner can use it to apply to the government of his country of origin for loss of original nationality, and does not function as proof that [the person] has already naturalised and obtained our country’s nationality. |

| 外國人於取得第一項準歸化中華民國國籍證明後,應檢附喪失原有國籍之證明文件,向住所地戶政事務所申請歸化,由該戶政事務所再查明其刑事案件紀錄,併送直轄市、縣(市)政府轉內政部。 | A foreigner, after obtaining preliminary proof of naturalisation to the nationality of the Republic of China under Paragraph 1, shall attach documents proving loss of original nationality to the application for naturalisation submitted to the household registration office in his place of domicile. That household registration office shall again ascertain [the applicant’s] criminal record, and then send [the documents] to the government of the special municipality or county (city) for forwarding to the Ministry of the Interior. |

| 外國人於取得歸化許可前,有不符本法所定歸化要件者,內政部應不予許可歸化。 | A foreigner who, prior to obtaining permission for naturalisation, did not meet the prerequisites for naturalisation under the law, shall not be granted permission for naturalisation by the Ministry of the Interior. |

The U.S. State Department does not regard this document as sufficient to trigger § 1481(a)(1). Nor do they afford such treatment to other similar documents issued by administrative authorities in other places (e.g. “approval-in-principle” letters issued by Hong Kong’s Immigration Department). Therefore, American emigrants who apply for naturalisation in these countries cannot enjoy no-fee relinquishment but instead have to renounce under § 1481(a)(5) and incur the State Department’s absurd fees.

Proposed reform

In December 2014, the Interior Committee of the Legislative Yuan considered various proposals for reforming Taiwan’s Nationality Law. One proposal they adopted would allow proof of loss of nationality to be submitted after naturalisation has been granted, allowing American naturalisation applicants there to escape State Department scalping. (I omitted the second half of the proposal, containing various exceptions for dual citizenship). This is part of the same package of reforms which would allow parents to give up citizenship on behalf of their adult children who lack the legal capacity to do so themselves.

第九條 |

Article 9 |

| 外國人申請歸化,應於許可歸化之日起,或依原屬國法令須滿一定年齡始得喪失原有國籍者自滿一定年齡之日起,一年內提出喪失原有國籍證明。屆期未提出者,應撤銷其歸化許可。 | A foreigner who applies for naturalisation shall, within one year from the day of permission for naturalisation, or of the day on which a person who under the law of his country of origin can only lose his original nationality upon reaching a certain age reaches that certain age, submit proof of loss of original nationality. For a person who has not submitted by the passage of that period, the permission for naturalisation shall be cancelled. |

| 未依前項規定提出喪失原有國籍證明前,應不予許可其定居。 | Prior to the submission of proof of loss of original nationality under the preceding paragraph, no permission for settlement shall be granted. |

“Permission for settlement” refers to household registration. In Taiwan, for historical reasons, household registration rather than nationality is the real source of what people usually call “rights of citizenship”. Many overseas Chinese who never had any connection with Taiwan, but retained allegiance to the old Republic of China after 1949, are “nationals” under the Nationality Law and consider themselves as such. They are entitled to Taiwan passports (which unfortunately don’t give them access to visa waivers in other countries) and a few other rights. Some of them have even moved to Taiwan, but that requires approval from immigration authorities, and for most practical purposes their rights in Taiwan are more similar to those of foreigners than locals. Under the Interior Committee’s proposal, newly-naturalised immigrants would first have this “national without citizenship” status until providing proof that they’d given up their previous citizenships.

In any case, the Interior Committee’s proposed amendments still haven’t become law yet, and in the meantime the existing “reasons not attributable to the person in question” dual-citizenship exception doesn’t help American emigrants in Taiwan — they still must go through the renunciation procedure under 8 USC § 1481(a)(5), for which the State Department charges a fee of US$2,350. The committee also adopted a resolution — proposed by Democratic Progressive Party members, but co-signed by Kuomintang and Taiwan Solidarity Union members as well — calling on the Ministry of the Interior to amend the regulations to add a “delay” exception like South Korea’s into the definition of difficulty in obtaining proof of loss of one’s original nationality:

| 為解決婚姻移民申請歸化而需提出「喪失原有國籍證明」時,可能遇有各類「非可歸責於當事人之事由」之困難,致無法取得該證明,或部份國家放棄國籍程序時間可能超過兩年,而使當事人無法及時提出該證明,故要求內政部應儘速修訂國籍法施行細則,明訂我國政府相關單位於一定期限內無法完成查證或取得其他國家的相關證明文件,即應視同構成「非可歸責於當事人之事由」,避免當事人因無法提出該證明而難以順利歸化。 | When marital immigrants applying for naturalisation must submit proof of loss of former nationality, they may encounter difficulties arising from “reasons not attributable to the person in question”, making them unable to obtain that proof. In some countries, the procedures for abandoning nationality may take longer than two years, causing the person in question to be unable to provide that proof on time. In order to resolve [this problem], we demand that the Ministry of Interior should amend the Nationality Law Implementation Rules as soon as possible, to clarify that the inability of the relevant organs and departments of our country’s government to complete the process of inspection or obtaining certificates or relevant documents of proof from other countries within a certain period of time, should also be regarded as “reasons not attributable to the person in question”, to avoid that inability to submit such proof would cause naturalisation difficulties for the person in question. |

| 提案人:李俊俋 陳其邁 尤美女 | Proposers: Lee Chun-yi, Chen Chi-mai, Yu Mei-nu |

| 連署人:段宜康 蕭美琴 陳學聖 黃文玲 | Co-signatories: Tuan Yi-kang, Hsiao Bi-khim, Shen Shei-saint, Huang Wen-ling |

The thing I want to know is this:

How did this “service” go from “no charge” (pre-2010) to $450USD out of the clear blue? Then, how did it jump to $2350USD? Are you saying that a service went from simple enough it was an actual free service being offered to US citizens (via taxes) to an extortion fee within 4 years? Let’s not forget the outright black-mailing of all other countries of the world, too…and they all caved! Why didn’t they all band together & give the USA the finger? The USA has a LOT of debt overseas– why not call that B.S., IRS money/power-grab for what it is? Keep it up, USA/IRS, & the next thing you know China’s will become the default currency.

This, is what you get when you (top 1% greedy d*ckheads) offshore the manufacturing, hoard your ill-gotten gains offshore, & then turn around to discover that there’s no more middle-class left to keep the country afloat!

The USA is becoming a police-state dictatorship.

@Tracy: Here’s my best guess. State Department said in 2010 when they first put the fee at $450:

https://www.federalregister.gov/articles/2010/06/28/2010-15622/schedule-of-fees-for-consular-services-department-of-state-and-overseas-embassies-and-consulates

I suspect what they really mean is that a tiny proportion of attempted renunciations (e.g. Ken O’Keefe, Bobby Fischer, Puerto Rican independence activists, etc.) took up an extraordinarily disproportionate amount of time, the rest are routine (“U.S. citizen? Don’t want to be one anymore? Got another citizenship already? Okay sign here and go deal with the IRS yourself cuz that’s not our job, next please!”), and they were going to let us routine ones cross-subsidise the extraordinary ones.

(It’s interesting that they still don’t charge a fee for 1481(a)(1) through (4) relinquishments, which are mostly more complicated than renunciations because they have to examine evidence to decide whether a relinquishing act actually occurred. I keep looking at this situation and feel like I must be missing something important, but I can’t figure out what.)

One other thing DoS said back then:

I believe it was Kevin Nightengale who pointed this out: four years later when DoS jacked up the fee, they must have thought that some part of the bolded section is no longer true:

1. DoS now wants to (or does not care if they) “discourage utilization of the service”; or

2. They no longer think that a high fee “discourage[s] utilization of the service”

@Eric,

I suspect they would like to charge for relinquishments if they could, but that there is some thin ethical string holding them back from doing so. I wouldn’t be surprised to find they start finding ways to push relinquishment cases into renunciation ones.

Alternatively, they can say, fine, relinquishing is free — but the processing fee for a CLN, if you need one, will be $2,350. After all, technically a CLN is not legally needed for relinquishers, right? So we’ll accept your relinquishment claim, but not issue a CLN unless you pay $2350.

@Eric…..Foo hit the nail “Alternatively, they can say, fine, relinquishing is free — but the processing fee for a CLN, if you need one, will be $2,350. After all, technically a CLN is not legally needed for relinquishers, right? So we’ll accept your relinquishment claim, but not issue a CLN unless you pay $2350.”

First, I am amazed how they can justify the fee to become a citizen is far less than getting rid of it. I think to become a USC its less than $1,000.

But I think Foo is on to something and frankly I wish they would jump in that tar pit.

A renunciation is straightforward and I do believe it should attract a basic fee. $450 does seem about right to process a renunciation.

For a relinquishment they do need to do some research and some actual work!! Maybe that should be the larger fee but make it clear that a CLN is indeed an optional but handy thing to have. If State started charging for a relinquishing CLN it would be far easier for people to provide self prepared and notarized affidavits.

I remember that Consulates provide Notary Services. Just thinking if someone went down and had the Consulate notarize a statement that you relinquished and gave that to a FI. hah…

@Foo, “I suspect they would like to charge for relinquishments if they could, but that there is some thin ethical string holding them back from doing so.”

They are being held back by the Expatriation Act of 1868 which they are now citing in the 7 FAM series.

But…….you did thread the needle because a CLN is indeed optional for nationality purposes.

@George: The CLN is only really optional if your other country doesn’t require it for you to obtain/retain their nationality (both countries discussed in the main post require it, as do many others). Re: getting the consulate to notarise a statement that you relinquished, sadly the State Department is way ahead of you. See 7 FAM 894:

In general terms, they can refuse to notarise any document which they think is for an “improper purpose” or is “inimical to the best interests of the United States”. They already use this authority, e.g. when asked to notarise applications for World Passports (7 FAM 1350)

On another note, I’d love to see US Foreign Service Officers paying US$7,050 out of their own pockets to every relinquisher if they later on try charging them a fee and it turns out to be illegal, per 22 USC 4209, “Exaction of excessive fees generally; penalty of treble amount”.

@Eric,

The State Department can say that it is optional under US law, which is all they are empowered to care about. But no problem, if you want one in order to comply with some other country’s (or bank’s) requirements, then fine, we’ll be happy to issue you one. That’ll be $2350, please.

Probably shouldn’t be giving them ideas. Though they don’t seem to need help in that department.

I hope the US jacks it up to $5000 or $10,000 making FATCA looking more and more absurd in front of foreign courts.

No one who happened to be born in the USA ever *consented* to the USA “laying claim” to them. How can they now charge to give up what was never consented to in the first place? Reminds me of this, quite a bit:

http://www.american-historama.org/1790-1800-new-nation/buying-freedom-from-slavery.htm

Such an interesting and good analogy, Tracy. Thanks for the link on emancipation.

@George, The US naturalization fee is $680, but first the person needs to be a permanent resident, which costs up to $580 for an initial petition plus $345 for the immigrant visa, depending on the category, plus $165 for the green card. The highest possible total is $1,770, which is still much less than the renunciation fee (except for investors, whose petition costs $1,500, so in this case the total would be $2,690, a bit more than the renunciation fee).

By the way, there is no cost to abandon permanent residence, it can be done by mail, and parents can do it on behalf of their minor children.

@Eric, @foo, I also wonder why there is no fee for relinquishment since the process is more complex than renunciation. Maybe it has something to do with the UN declaration of human rights, which states that people have the right to change their nationality, but not necessarily to abandon a nationality if they have more than one, or to become stateless.

When asked why he renounced in 2006, Mr. Gilliam replied, “The reality is, when I kick the bucket, American tax authorities assess everything I own in the world—everything I own is outside of America—and then tax me on it, and that would mean my wife would probably have to sell our house to pay the taxes. I didn’t think that was fair on my wife and children

Quote from Terry Gilliam the only American member of Monty Python when asked in 2006 why he renounced his US citizenship. Terry was born in Minneapolis and is now 74 years of age.

I would have assumed that being forced to be relieved of the US citizenship could be grounds for relinquishment—-if the process were to first allow gaining that new citizenship with the intention of losing the last. But I doubt it works that way