|

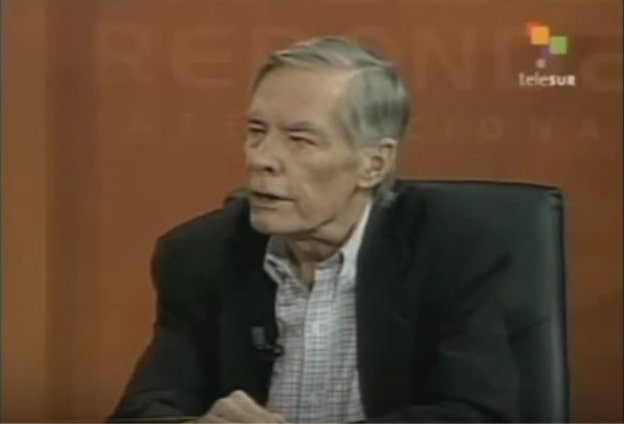

| Agee in a 2007 interview with TeleSUR’s Mesa Redonda in Cuba |

With all the attention suddenly being paid to China’s policy of forbidding Hong Kong dual citizens from using foreign passports to enter & leave mainland China unless they renounce Chinese citizenship (by mailing a form to the Hong Kong Immigration Department and paying US$19), it’s worth taking another look at the origins of the U.S. policy of forbidding U.S. dual citizens from using foreign passports to enter & leave the U.S. unless they renounce American citizenship (by waiting ten months for a consular appointment and paying US$2,350).

As mentioned last year, Ted Kennedy and Alan Simpson had to lie and obfuscate to get this policy made into law (8 USC § 1185(b)); prior to their change, it was legal for U.S. citizens to use foreign passports to enter and leave. Kennedy vaguely mentioned “technical challenges to application of the Travel Control Regulations by United States citizens who enter or leave the United States using foreign passports” as a reason for the ban, without explaining what he meant. One theory was that Kennedy & Simpson were aiming at the suddenly-increasing number of Americans naturalising in foreign countries — after losing various court cases in the 1980s to people who wanted to keep U.S. citizenship (e.g. Vance v. Terrazas, 444 U.S. 252 (1980); Kahane v. Shultz, 653 F. Supp 1486 (E.D.N.Y., 1987)), in 1990 the State Department adopted a new policy of assuming that Americans abroad intended to keep U.S. citizenship even if they committed relinquishing acts such as becoming a citizen of another country or working for its government.

But around the same time as Terrazas, another American abroad lost a case in the U.S. Supreme Court: Haig v. Agee, 453 U.S. 280 (1981). That case wasn’t about U.S. citizenship per se, but about the right to a U.S. passport. And it was not a victory for “rights of citizenship”: SCOTUS ruled that State could cancel the U.S. passport of ex-CIA employee Philip Agee. Agee remained abroad for some years, but by the late 1980s he was travelling in and out of the U.S. freely by entering through the Canadian border and then returning to Europe on a Nicaraguan travel document and later a German one (his wife Giselle Roberge was a dancer for the Hamburg Ballet).

Agee was, undoubtedly, the most high-profile U.S. citizen at the time who used non-U.S. travel documents to enter and leave the United States, and who thus would have been affected by Kennedy & Simpson’s new U.S. passport requirement. However, at the same time, other politicians were pushing to use passport revocation for enforcing child support orders — which might have made them notice that, under the law at the time, such revocation would be ineffective against dual citizens, who could get passports from other countries.

So in this post, we’ll look at the evidence: was Agee the specific person Kennedy & Simpson had in mind when they enacted the foreign passports ban? Why didn’t the government enact the ban earlier? And did this provision actually have any effect on Agee’s travels to the United States, by making him afraid he wouldn’t be able to leave again after he’d entered?

Table of contents

- Background: Agee’s activities, 1968–1987

- Congress & State start paying closer attention

- The other theory: passport revocation for unpaid child support

- Aftermath

- Conclusion

Background: Agee’s activities, 1968–1987

Leaving the CIA

Agee worked for the CIA until he became disillusioned about his work and quit in 1968. Seven years later, while living in London, he published the first of his five books about the CIA, Inside the Company. Agee’s books revealed a great deal of information about his old job, including the names of then-current agents. That ultimately led to his deportation from the United Kingdom. He eventually ended up in Hamburg, Germany. After his second book, Dirty Work, the State Department revoked his U.S. passport on the grounds that his activities “caused serious damage to the national security and foreign policy of the United States”.

Agee’s response was to sue the State Department. His case went to the Supreme Court: Haig v. Agee, 453 U.S. 280 (1981). (Note that Agee’s name appears second: he was the appellee, with the government appealing the DC Circuit’s decision in his favour.) Seven justices voted to reverse the lower courts, ruling that the State Department’s decision to revoke Agee’s passport violated neither the Constitution nor the passport statutes.

SCOTUS allowed State to burden Agee’s right of international travel, but it did not give State the right to demand Agee come back from overseas — Congress granted that power to the judiciary (see Blackmer v. United States, 284 U.S. 421 (1932)), but not the executive. The executive didn’t even have the power to trap Agee in the U.S. if he came voluntarily, absent criminal charges and a court order for him to stay. A passport was not actually a prerequisite to leave the United States, let alone to remain abroad; its withdrawal did not illegalise the former bearer’s absence from the United States. Joy Beane, Passport Revocation: A Critical Analysis of Haig v. Agee and the Policy Test, 5 Fordham Int’l L.J. 185, 188 (1981):

14. See Lynd v. Rusk, 389 F.2d 940, 947 (D.C. Cir. 1967); See also Proposed Travel Controls: Hearings on S3243 Before the Subcomm. to Investigate the Administration of the Internal Security Act and Other Internal Security Laws of the Senate Comm. on the Judiciary, 89th Cong. 2d Sess. 56 (May 17, 18, 19, 1966) (remarks of Rep. Sourwine) (hereinafter cited as 1966 Hearings on S3243). Representative Sourwine noted that passport regulation did not become travel control until a passport was made a prerequisite of travel abroad.

That is to say, the withdrawal of a U.S. passport did not mean withdrawal of permission to remain abroad (since no one needs that permission from the government in the first place), and under the laws of the time it didn’t even mean withdrawal of permission to enter and leave. All it meant was that the Secretary of State had the power to stop asking “all whom it may concern to permit [Agee] to pass without delay or hindrance and in case of need to give all lawful aid and protection”. As the Supreme Court stated:

In Cole v. Young, supra, we held that federal employees who hold “sensitive” positions “where they could bring about any discernible adverse effects on the Nation’s security” may be suspended without a presuspension hearing. 351 U.S. at 351 U.S. 546-547. For the same reasons, when there is a substantial likelihood of “serious damage” to national security or foreign policy as a result of a passport holder’s activities in foreign countries, the Government may take action to ensure that the holder may not exploit the sponsorship of his travels by the United States.

This distinction is important: passport revocation was not originally travel control — as long as you could find another government to “sponsor your travels”. It was Kennedy and Simpson who turned passport revocation into full-scale travel control by restricting the right to leave the country to those who obtained a document which could only be obtained from the U.S. government. They made the U.S. government the sole arbiter of whether a citizen would be allowed to leave. (As the U.S. passport requirement only applies to U.S. citizens, you could always try to exempt yourself from it by renouncing citizenship from within the United States under the Renunciation Act of 1944, but no one’s had much success at that lately.)

First U.S. visit after passport revocation

Agee’s first visit to the U.S. after State lifted his U.S. passport was in 1987. At the time he had what reports described as a Nicaraguan passport (though I think it may have been a non-citizen’s travel document), and crossed into the U.S. via Canada. (It has always been legal — and remains so even today — for a U.S. citizen to enter the U.S. from Canada without a U.S. passport, as long as you have an “acceptable” proof of citizenship & identity, and back before the Western Hemisphere Travel Initiative they were far more lax about what constituted “acceptable” proof.)

Since Agee had previously been determined to be a U.S. citizen and had never renounced citizenship, he would not have been able to obtain a U.S. visa on any of those documents; instead, the State Department appears to have issued him some sort of non-passport documentation which confirmed his identity and citizenship. At the time, the Associated Press reported that “[a] State Department press officer, Ruth van Heuven, said Agee’s return to the United States without a U.S. passport violates no laws.” State might have thought his subsequent departure on a Nicaraguan passport was illegal, but of course State got it wrong: a U.S. passport was not required until 1994.

(Minor tangent: Van Heuven handled some of the on-the-ground work related to the revocation of Agee’s passport back in 1979; she and her husband were stationed in Bonn at the time. Van Heuven herself is the daughter of two Swiss emigrants to the United States. Switzerland never seemed to have thought it was worth trying to trap her in the country and go through her pockets to see if she had anything worth taking when she came to visit Grandma & Grandpa. You can read all about it in her interview with the Association for Diplomatic Training and Studies’ Oral History Project.)

Congress & State start paying closer attention

1990: State learns what 1185(b) really says

Though the State Department sometimes tried to claim (e.g. in Matter of L.J.M., 14 BAR(D) 288, 300 (1987)) that 8 USC § 1185(b)’s requirement for a “valid passport” on arrival & departure actually meant a “valid U.S. passport” and could not include a “valid foreign passport”, a few years later the DC District Court tacitly admitted that this was wrong and that the law did not bar a U.S. citizen from departing the United States on a foreign passport. The case in which they admitted this was filed by none other than Philip Agee himself, as part of his post-Haig v. Agee efforts to get a new U.S. passport: Agee v. Baker, 753 F.Supp. 373 (D.D.C., 1990).

The law generally requires that a citizen hold a valid passport to enter or depart from the United States, 8 U.S.C. section 1185(b), although the United States has regularly since 1987, and says it will again, issue Agee an identity card allowing him to enter the country. But with his Nicaraguan passport revoked, Agee may not be able to return to Spain or elsewhere abroad if he comes here.

Note the dog that did not bark: neither the court nor the executive claimed that Agee was breaking the law by using that Nicaraguan passport to depart from the United States.

The State Department’s Office of the Legal Adviser helped draft the government’s brief in the case; they did not try to claim that Agee’s earlier departure from the U.S. without a U.S. passport had been unlawful, but wrote solely on the issue of whether he “may travel under the sponsorship of the American government” and whether State had followed proper procedures. State later devoted several pages to this case in the Digest of United States Practice in International Law, 1989–1990. Agee wrote in 1992 that after he obtained a certificate of identity (i.e. alien’s travel document) issued by Germany, he withdrew his U.S. passport application to avoid wasting more time and money.

If it really was the State Department which got Kennedy and Simpson to put the foreign passport ban into the “technical amendment”, whoever suggested it might have had this case in mind, especially given that they tried to justify it by invoking fears of “technical challenges to application of the Travel Control Regulations by United States citizens who enter or leave the United States using foreign passports”. I haven’t been able to find any other court cases involving 8 USC § 1185(b) or 22 CFR 53 in those years.

However, I doubt this case was the main trigger for the amendment in the first failed 1993 “technical corrections” bill, just a step along the way towards it. All of the above events occurred during the Reagan and Bush I administrations. Bush I in particular would likely have been looking for any way he could to stop Agee from freely visiting the United States: Bush was an ex-CIA director, and he blamed Agee for the assassination of the CIA’s Athens station chief Richard Welch. (Agee responded to that by pointing out that the U.S. government had already warned Welch his house might be unsafe; when Barbara Bush repeated the accusation in her memoirs, he sued her for libel, and she removed it from the next edition as part of a legal settlement.) Yet no bills in the 102nd Congress included any provisions restricting the use of foreign passports to depart the U.S., as discussed previously.

1993: The Halperin nomination

About a month before Kennedy and Simpson introduced their first “technical amendments” bill (the one that didn’t pass) in July 1993, Philip Agee’s name came up on Capitol Hill in a different context: the Clinton Administration’s nomination of former American Civil Liberties Union director Morton Halperin to be Assistant Secretary of Defense for Democracy and Peacekeeping.

When Halperin stepped down as ACLU director in 1992, he received praise from Democrats and Republicans alike. See speeches by Orrin Hatch (3 Oct., 138 Cong. Rec. S16512), Joe Biden (8 Oct., S18229), and Ted Kennedy (29 Oct., S18273). However, the following year, other Republicans began speaking out against the Halperin nomination even before it was announced formally, as the Washington Post reported:

Former Reagan Pentagon official Frank J. Gaffney Jr. is spearheading the opposition. He said he keyed his opening salvo against Halperin last June — three months before he was formally nominated — to the president’s statement that he pulled Lani Guinier’s Justice Department nomination because he couldn’t agree with her writings. Gaffney has distributed what he acknowledged yesterday to be a “somewhat selective” rendition of Halperin’s writings, “to give a flavor to people of the kinds of controversial views and advocacy he had been associated with for decades.”

One of the major accusations against Halperin was that he had aided Agee’s campaign against the CIA. As the WaPo notes, Gaffney first brought this up in a June 1993 op-ed, and expanded on that theme in his September 1993 letter to President Clinton.

So my best guess on how the foreign passports ban ended up in the Senate’s 1993 “technical corrections” bill, and then the 1994 bill in which it actually became law, is that someone whose ear Gaffney had — most likely a Republican, though some Democrats also spoke out against the Halperin nomination — heard about Agee in that context, realised that Agee was still actively visiting the U.S. and speaking there, and started trying to think of ways to stop him. Alternatively, it’s possible that the proposal for a foreign passport ban had been bouncing around within State ever since the Bush I administration, and then someone in the Clinton administration seized on the proposal and got it inserted into that bill to try to prove that they weren’t soft on Agee, in a (failed) effort to prevent that issue from derailing Halperin’s confirmation.

One odd tangential piece of evidence which I don’t know how to interpret: the relationship of Kennedy and Halperin to the Intelligence Identities Protection Act, the 1981 law which tried to criminalise books like Agee’s. According to investigative journalist Angus McKenzie’s description in his Secrets: The CIA’s War at Home (University of California Press, 1999), Kennedy made various unsuccessful efforts to soften various provisions of the law, while Halperin gutted the ACLU’s efforts to protest against the law (pp. 83–85).

The other theory: passport revocation for unpaid child support

Another possibility is that the Kennedy–Simpson foreign passports ban was connected to efforts towards revoking the U.S. passports of parents with unpaid child support. Supporters of those provisions stated in floor speeches that they wanted to prevent such parents from fleeing the country with unpaid bills — but of course, without any legal requirement that departing citizens must hold U.S. passports, some of their targets would be able to circumvent the attempted travel ban by obtaining foreign passports. On its face, this seems like the more staid & plausible theory — it doesn’t involve any tales of international intrigue from Hamburg to Havana. On the other hand, the timeline doesn’t make much sense, and Kennedy doesn’t appear to have been very enthusiastic about the child support enforcement bills in the first place.

The push to give the federal government more powers to use for child support enforcement which eventually led passport revocation began in the late 1980s with the Family Support Act of 1988. That act established the Interstate Commission on Child Support, which gave regular reports to Congress, but as far as I can see the idea of passport revocation didn’t come up in the hearings on child support enforcement during the early 1990s (see e.g. S. Hrg. 102-441, September 1991; Serial 102-98, August 1992).

Passport revocation seems to have first appeared as part of H.R. 1961 in May 1993, just a couple of months before Kennedy and Simpson first introduced the foreign passports ban. However, H.R. 1961 didn’t make it out of committee, nor did H.R. 4570 the following year, nor did H.R. 95 in July 1995. The first time passport revocation showed up in the Senate seems to have been S. 442 in February 1995. Simpson joined that bill’s bipartisan list of co-sponsors in March, but Kennedy did not; anyway it died in committee. There was also S. 687 in April and S. 746 and S. 828 in May, but none had any cosponsors and all got ignored by the Committee on Finance. Simpson and 31 other Republicans co-sponsored S. 1120 in August, but Kennedy did not co-sponsor S. 1117, a Democratic counterpart to that bill. The Senate actually voted on passport revocation with H.R. 4; Kennedy voted against both the Senate’s version of the bill and the version that came out of conference. For what it’s worth, Simpson voted in favour both times, but it didn’t matter anyway: Clinton vetoed it and the Republicans couldn’t gather enough votes to override the veto. Simpson also voted in favour, and Kennedy voted against, H.R. 3737, the bill that actually made the passport revocation provision into law.

In short, Kennedy and Simpson seem to have disagreed about the child support enforcement bills, and the matter got heavily tied up in partisan politics — so I don’t think the two men are so likely to have cooperated on the foreign passports ban in 1993 & 1994 if its ultimate goal was to provide back-up for those controversial child support enforcement bills.

Aftermath

Government shutdown causes breach of human rights treaty

For whatever reason, the foreign passports ban became law in 1994, and, as noted by Daniel Patrick Moynihan, resulted in a breach of the U.S.’ obligations under the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights two years later during the 1995–1996 federal government shutdown, when it became impossible for U.S. citizens to obtain new U.S. passports for nearly a month:

Today, the Washington Post reports that the Government closing has created a backlog of 200,000 passport applications. This is no way to begin a record-breaking year at the Passport Office.

Speaking of the backlog of passport applications is perhaps too callous. All of these applications were submitted by citizens who expect that the Federal Government will provide them with a passport so they can travel to other countries to conduct business, study, visit family and friends, and vacation. Two hundred and fifty constituents have contacted my office seeking assistance; however, the passport office will only issue passports in cases considered life or death emergencies. One man was unable to attend his daughter’s wedding in London because his passport had expired and could not be renewed. Another who is employed abroad fears losing his job if he cannot get his passport renewed. For years, we badgered the Soviet Union to grant more passports to its citizens. Now we are denying them to our own.

Article 12 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, ratified by the U.S. Senate on April 2, 1992, recognizes that “Everyone shall be free to leave any country, including his own.” This is a binding international obligation of the United States, yet we have now taken action which violates that covenant.

A 1- or 2-day delay might be considered a nuisance. For this to continue for 3 weeks leads to incalculable waste, as people are forced to cancel plans and seek refunds for reservations. This is not just. Closing passport offices and other large swaths of the Federal Government erodes the confidence of all Americans, disrupts the lives of those who rely on Government services, and discourages Federal workers. Clearly we have entered an Orwellian realm in which employees are paid not to work so that negotiations to save money can continue.

The U.S. government shut down again in 2013 for another 16 days, but that time user-fee-funded services — including passport issuance — continued to operate. The FBI continued updating its NICS gun control database during that period, though during the shutdown they did not issue a report on the number of new records added. IRS employees reported to work — except for the employees whose job is to protect taxpayer rights.

Agee visits U.S. a few more times, and then stays abroad

I’m not able to figure out exactly when Agee’s final visit to the U.S. was; the Los Angeles Times wrote in 1997 that “he apparently has traveled in and out of the United States without difficulty and has made numerous public appearances in this country”. (Agee was often at odds with the LA Times after they published Cuban defector Florentino Aspillaga Lombard’s allegations against him, so it’s possible they were exaggerating). He definitely did visit the U.S. at least once after the effective date of the 1994 “technical amendments”, to speak at Cal State Chico on his book; C-SPAN broadcast video of the event.

I don’t see any sources indicating that Agee visited the U.S. again after he started his travel company Cuba Linda, though if indeed he stayed away it was probably for fear of prosecution by the Bush II administration over alleged violations of sanctions against Cuba, rather than fear of passport-related exit controls. Even after the Intelligence Reform and Terrorism Prevention Act of 2004 (S. 2845) and the Western Hemisphere Travel Initiative tightened things up even further, Agee could always have left the U.S. through Mexico. He remained well enough to travel to Ireland for a speaking tour the year before his death. Leonard Weinglass, a lawyer for the Cuban Five (among them René González, who’s been mentioned here several times as yet another example of someone who renounced U.S. citizenship and never showed up in the Federal Register), wrote that he met Agee several times while visiting Cuba, but says nothing of any reciprocal visits by Agee to the United States.

Despite remaining outside the U.S., Agee retained his U.S. citizenship; his son Chris, who teaches at CUNY, says that his father “never renounced his U.S. citizenship because his work was all about building a more active sense of citizenship among his fellow U.S. citizens”. Something else that probably played a role: Homelanders don’t think that people who live abroad for most of their lives are “true Americans”, and probably wouldn’t listen to what such people had to say about the U.S. — especially if they confirmed their lack of “American-ness” by renouncing citizenship — and Agee remained committed until the end to getting the Homeland to listen to his accusations against the CIA.

Conclusion

In 1961, Francis Walter of the House Un-American Activities Committee shifted the burden of proof for expatriation to the party claiming loss of nationality in an apparent effort to facilitate the prosecution of treason cases, and half a century later the State Department uses his law to tell people who had lived their lives as sole citizens of Australia for more than two decades that there was “insufficient evidence” to suggest they no longer wanted their U.S. citizenship. Bush II acquiesced to Treasury’s demands for tightened FBAR enforcement on the theory that it could be used to fight terrorist financing, and eight years later Canadian grandmas were paying five-figure fines against two and three-figure annual U.S. tax deficiencies.

And most recently, Congress has taken what was probably a national security provision first aimed at someone they saw as a a threat to CIA agents abroad, and used it as the basis for trapping emigrants in the U.S. when they come back for a visit and forbidding them from going back to the country where they actually live until they pay what the IRS claims they owe. The U.S. government may have major barriers in the way of actually enforcing the U.S. passport requirement on departure, but they can overcome those through mere executive action, without any further approval by Congress aside from funding.

Here at Brock we have emigrants and accidentals with no U.S. party affiliation at all and a wide variety of views on U.S. foreign policy, as well as Democratic and Republican readers from the United States and other countries. But no matter what you think about Philip Agee’s actions and politics, one thing is clear: time and again, Congress passes laws which purport to protect the U.S. against its alleged enemies (typically while lying about the details of what those laws do), and then they use those laws as the foundation for a campaign of harassment against ordinary members of the diaspora, all while the U.S. media claim that other countries’ far narrower actions along the same lines are violations of human rights and international agreements.

Thank you Eric fir your continued work. Very interesting.

Mine’s probably the last generation to remember being able to enter and exit the US with just a smile.

@ Eric

What a fascinating tale about Philip Agee and the machinations of the US government. It makes me want to read Agee’s books about the CIA, written from his perspective as a disillusioned former agent. It’s amazing the contortions and distortions involved in the effort to prevent Agee from entering the USA to spread his message about the CIA. While swatting at the Agee fly in their ointment the congress critters stomp all over the freedom of movement of untold others which are merely collateral damage to them. WAIT … this sounds familiar … like the FATCA fiasco.

@Eric

Fabulous post! Did anybody ever suggest that you should become a researcher/writer when you grow/grew up? Seriously great stuff!

I came across the following about issuance of passports that is of some interest:

https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/22/212

which reads:

22 U.S. Code § 212 – Persons entitled to passport

Bit of discretion granted there …

@Eric–practically speaking, the US still has no exit immigration, so who’s to know what passport you’re leaving on?

@socrates: “still” is the scary word in that sentence. They’re working on implementing exit checks, slowly. (If Trump gets elected, expect “slowly” to speed up quite a bit, since exit checks are closely tied to detecting visa overstayers.) Won’t be done now, or even next year, but it’ll be done within the lifetimes of most DIY relinquishers.

http://isaacbrocksociety.ca/2015/08/11/closer-scrutiny-of-international-departures-at-ten-u-s-airports-u-s-citizens-trying-to-leave-without-u-s-passports-may-face-questioning/

Latest report is, they’re testing facial recognition for passengers on ATL–NRT flights:

https://web.archive.org/web/20160703074604/https://www.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/publications/privacy-pia-cbp-dis%20test-june2016.pdf

If you use a US passport to check in to the flight, they just compare the picture they take of you at boarding to the picture in the passport you used to check in, and then delete it once they confirm. But say you’re a US citizen using a non-US passport to check in for the flight. Then initially they don’t know you’re a US citizen, so they claim they have the right to compare your photo against big database of “other DHS encounters”.

If that matches against some previous photo of you in their database indicating that you’re a U.S. citizen, then you’ve just been detected as violating 1185(b). I wouldn’t expect the “other DHS encounters” photo database to include every US passport photo in existence, but it might well include the photos from revoked US passports.

‘If you use a US passport to check in to the flight, they just compare the picture they take of you at boarding to the picture in the passport you used to check in, and then delete it once they confirm. But say you’re a US citizen using a non-US passport to check in for the flight. Then initially they don’t know you’re a US citizen, so they claim they have the right to compare your photo against big database of “other DHS encounters”.

If that matches against some previous photo of you in their database indicating that you’re a U.S. citizen, then you’ve just been detected as violating 1185(b).’

Not detected, maybe suspected but maybe not. When checking in for a flight, the airline has a reason to check if Japan will let the person in rather than deport the person at the airline’s expense. So even when I was a US citizen and used my US passport to go through US immigration, I presented my Japanese reentry permit stamped in my Canadian passport to airline personnel when checking in to depart the US. If the US had immigration checkpoints for departures, I would have presented my US passport to US immigration.

Wonderful post, Eric! Although it doesn’t make my exile any easier it’s good to know the background of the situation.

I do have a concern about your statement, ‘It has always been legal — and remains so even today — for a U.S. citizen to enter the U.S. from Canada without a U.S. passport, as long as you have an “acceptable” proof of citizenship & identity,…’: I read the link you provided and this appears to apply only to people with NEXUS cards or one of the other available “closer connection” cards. All one’s citizenship information has to be divulged to get one of those cards. Otherwise, as I understand it, a US passport IS required to cross the Canada/US border.

The “western hemisphere” (cruise ship) travel exemption assumes that the travel originated in the United States. If I were to take an Alaska cruise from Vancouver I would have to present a US passport upon boarding.

If I’ve misunderstood the regulations as provided in the link, I’d love further discussion on this.

Thank you, Eric!

@ MuzzledNoMore

Here’s some nifty info for Canadian sun seekers …

http://turksandcaicostourism.com/immigration-turks-and-caicos-entry-requirements/

CANADIAN CITIZENS

Visitors from Canada may enter the Turks and Caicos without a passport, if they meet the following conditions:

Traveling (entry and departure) DIRECT from Canada into the Turks and Caicos

Is carrying an original [or notarized copy] of their birth certificate

Is carrying a valid government issued photo id

If the traveler does not meet all three of these requirements, they will be required to have a valid Canadian passport.

Unfortunately “born in the USA” is still a problem with these alternate requirements … and you would not want your plane to be blown off course into US enemy territory. Hmm … car tour of Central and Eastern Canada (or bus or train) and then a $400 to $600 (WestJet return fare) direct flight from Halifax to T&C … sigh … just dreaming.

Not exactly related to the main post, just dumping some excerpts from this disgusting speech I stumbled across by Travel Control Teddy explaining why your Canadian house should be subject to the US exit tax:

https://www.congress.gov/congressional-record/1995/7/10/senate-section/article/s9602-1

1812 … gee, didn’t some country or another fight some war that year complaining about refusal to recognise the right of expatriation? Guess they must have lost that war cuz the right is clearly dead and gone.

Incidentally, I am grateful to see that someone in academia looked into this issue (to at least some extent) back when it was current. H. Angsar Kelly. “Dual Nationality, the Myth of Election, and a Kinder, Gentler State Department”. 23 Inter-American Law Review 421, 423 (1991–2).

“Hmm … car tour of Central and Eastern Canada (or bus or train) and then a $400 to $600 (WestJet return fare) direct flight from Halifax to T&C … sigh … just dreaming.”

Didn’t CN Rail from Montreal to Halifax formerly pass through the US? Was the route changed when the US built its copy of the Berlin Wall?