Recently, newspapers in the Philippines have reported on accusations that National Food Authority administrator Orlan Calayag is still a U.S. citizen. For example, The Philippine Star writes that Calayag “acquired dual citizenship as American and Filipino on Jan. 7, 2013”, while the Manila Standard Today quotes an unnamed source who claims that Calayag “reacquired Philippine citizenship … but still did not renounce his US citizenship”.

However, the people they quoted are missing a crucial fact: in August 2013, the U.S Internal Revenue Service (IRS) confirmed in an official notice that one Orlan Agbin Calayag had given up his U.S. citizenship. Calayag was one of more than a thousand people whose names appeared in the IRS’ most recent official list of newly-minted ex-U.S. citizens. Most of them seem to have given up U.S. citizenship sometime between mid-2012 and early 2013.

Whether or not Calayag is a natural-born citizen of the Philippines (a question of Philippine law on which I take no position), he is definitely no longer an American or a dual citizen.

Public U.S. government list of certain ex-citizens

This list — the “Quarterly Publication of Individuals Who Have Chosen to Expatriate” — is printed four times per year in the U.S. government’s official gazette, the Federal Register. The IRS compiles this list as part of the process of checking that everyone giving up U.S. citizenship has sent in their final U.S. tax payment — it’s the IRS’ last chance to assess taxes and levy fines for failure to report non-U.S. bank accounts and other financial assets.

Not everyone who gives up U.S. citizenship appears in this list. As Canada’s Global News recently reported, the Federal Bureau of Investigation maintains its own partial list of people who have given up U.S. citizenship, for the purpose of administering U.S. gun control laws, and just last year the FBI list added more than four times as many names as the IRS list. However, everyone who appears in this list is definitely an ex-U.S. citizen.

Other Philippine politicians who have appeared in the “Quarterly Publication” include Senator Alan Peter Cayetano (1st quarter, 1999) and mayoral candidate Vicente Dumadag Abobo (2nd quarter, 2010). There’s probably also others whose names I have missed.

Why would someone give up U.S. citizenship?

Whenever a politician or other public figure says he has given up U.S. citizenship, many members of the public respond with disbelief. They imagine that he is just keeping his U.S. passport buried somewhere and will dig it up again when no one is looking.

In fact, these days increasing numbers of U.S. citizens residing outside the U.S. are finding that their U.S. citizenship is more of a burden than a benefit, and have decided there’s no reason to keep it if they never plan to move back to the United States. Not everyone who comes to this realisation immediately goes out and quits U.S. citizenship — but when faced with a major life event, like the birth of a child or the offer of a great new job, they sit down and think about things, and find that on balance they’d be better off without U.S. citizenship.

The new extraterritorial FATCA law is a big reason — it’s making it difficult for U.S. citizens abroad to keep bank accounts and mortgages where they live. Compliance with FATCA would violate Philippine banking laws and the Constitution, as Ateneo de Manila Law School Professor Edzyl Josef G. Magante revealed previously. However, instead of refusing to comply with FATCA, Philippine banks, operating solely in the Philippines, have demanded that the Department of Finance and the BSP sign an “Inter-Governmental Agreement” to exempt them from Philippine law so they can obey foreign law instead.

What other documents prove you gave up U.S. citizenship?

Because the “Quarterly Publication” does not contain the name of every person who gives up U.S. citizenship, nor any other identifying details about the people who do appear (like their birthdate and other citizenship), the U.S. government issues other documents for people to prove that they are no longer U.S. citizens. The most common of these is the Certificate of Loss of Nationality (“CLN”, officially Form DS-4083). See the pictures & explanations below.

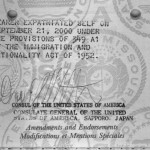

The cancelled U.S. passport of an ex-citizen may contain a typed or handwritten note that “bearer expatriated self”. The picture above belongs to the former David Aldwinckle, a.k.a. Arudou Debito, who gave up U.S. citizenship in 2002 after naturalising in Japan. |

Mark Snider, U.S. Consul-General in Lahore, wrote a letter on official stationery confirming that Pakistani politician Fauzia Kasuri gave up U.S. citizenship in March 2013. However, others who ask for such letters have had their requests refused, and are told to wait for their official CLN instead. |

CLN issued to Canadian citizen & Isaac Brock Society founder Peter Dunn. Dunn chose to give up U.S. citizenship in February 2011, and his name appeared in the “Quarterly Publication” for the 3rd quarter, 2012. |

Additionally, some people may be required to pay a US$450 consular fee to exercise the right to give up U.S. citizenship; those who were required to pay will generally get a receipt from the consulate to indicate that they have paid the fee. However, not everyone has to pay this fee, and those who did not will not have such a receipt. This depends on the rather technical matter of which paragraph of 8 USC § 1481(a) applies to their case. In the end, whether or not you paid the fee makes no difference to your legal status: you have still irrevocably given up your U.S. citizenship.

Genuine & irrevocable way to give up U.S. citizenship

Letting your U.S. passport expire, making a declaration before a notary public or a court, or filing a Philippine affidavit of renunciation (what Rommel Arnado did) has absolutely no effect on U.S. citizenship. The U.S. government accepts only one procedure for giving up U.S. citizenship: filing Form DS-4079 and/or Form DS-4080 to inform a U.S. consulate or embassy that you have committed one of the “expatriating acts” listed in 8 USC § 1481(a) and that you intended to give up U.S. citizenship.

Once you have informed the consulate of this, they will punch holes in your U.S. passport and issue a finding that you lost U.S. citizenship. Loss of citizenship is effective as of the date that you committed your “expatriating act”, not as of the date you reported to the consulate. The consulate may also forward your details to the IRS, so that the latter agency can check on your tax compliance and possibly add your name to the “Quarterly Publication”.

Afterwards, you can no longer claim any of the rights of U.S. citizenship. In particular, if you genuinely gave up U.S. citizenship, the consulate will punch holes in your U.S. passport to invalidate it, and you cannot apply for a new one. To travel to the U.S. again you must apply for a U.S. visa< on a Philippine or other passport, just like any other non-citizen. If you want to re-acquire U.S. citizenship, you must start from the very beginning by standing in line for a new green card.

So when exactly did Calayag give up U.S. citizenship?

The only way to know for sure is to ask him to show you his Certificate of Loss of Nationality. The “Quarterly Publication” will not tell you. At minimum, everyone in the “Quarterly Publication” gave up citizenship at least three months before the date of publication, and it’s not unusual for it to take a year or two for names to show up. In one extreme case, feminist scholar Shere Hite gave up U.S. citizenship in early 1996, but her name didn’t get printed until late in 2001.

There are four other politicians in the same list as Calayag, who are known (from media reports) to have given up U.S. citizenship between mid-2012 and February 2013: Naftali Bennett and Dov Lipman of Israel, and Bernard Chan Pak-li and Erica Yuen of Hong Kong. In contrast, Pakistani politician Fauzia Kasuri and Hong Kong investment banker Marshall Nicholson, who gave up U.S. citizenship in March and April 2013, did not make the cutoff to appear in the same list as Calayag.

Conclusion

It is clear that Orlan Agbin Calayag is no longer a U.S. citizen. Under international law, every country has the sole right to determine who its own citizens are, and the U.S. government itself has officially stated that Calayag has ceased to be a U.S. citizen. Now, whether or not he meets all the other requirements to hold his position as administrator of the National Food Authority — in particular, the requirement that he be a natural-born Philippine citizen on the date of his appointment — is a question of Philippine law in which other countries have no say.

Hmm:

” Loss of citizenship is effective as of the date that you committed your “expatriating act”, not as of the date you reported to the consulate”

I have been told the opposite, that the loss occurs when reporting to the consulate. So which is correct?

For tax purposes (Title 26), the IRS holds that your “expatriation date” for computing the exit tax is “the date the individual furnishes to the United States Department of State a signed statement of voluntary relinquishment of United States nationality confirming the performance of an act of expatriation” (26 USC 877A(g)(4)).

However for nationality law purposes (Title 8), your CLN will list your date of loss of citizenship as the date you performed the expatriating act. People here have obtained “back-dated CLNs”: these confirm that they lost U.S. citizenship in the 1970s or 1980s when they naturalised as Canadian citizens. The “approval date” listed at the upper-right of the CLN is current, while the “expatriation date” listed in the middle is that year in the 1970s/1980s.

“You may well wonder why this list of individuals who have sworn off allegiance to the United States is published by the Internal Revenue Service and not by the State Department, especially when it is the State Department that issues the “Certificate of Lost Nationality” that results when a person has gone through the difficult process of renouncing their US Citizenship.

The reason for the IRS handling the list is because the 1996 law (PL 104-191, Title V, Sec 512(a)) was passed in an atmosphere where it was assumed that tax evasion was the number one reason for renouncing one’s US citizenship.”

http://askasl.blogspot.ca/2010/02/list-of-americans-who-have-renounced.html

The conditions on the ground tell a different story, but unfortunately the stigma remains.

On this question of which date is valid, I have suggested that it is a contradiction in law, and in my opinion, shouldn’t hold up to scrutiny in a court of law. For how can one be still a citizen for tax purposes but not a US person? It is a ridiculous attempt by lawmakers to have it both ways. But they have not gone back to the part of the tax code which defines a US person as a citizen or resident of the United States. Thus, there is a serious contradiction.

The idea that a person could be taxed by a country of which they are neither a citizen or resident is also a major violation of the Universal human rights, to say the least. Everyone has a right to change citizenship. That right rests with the person and not with the state. I determine when and how I am no longer a citizen–and I co-operate with the procedures of the state if it does not inconvenience me too much. The United States has become a laughing stock.

I wonder if Boris Johnson (Mayor of London) has renounced yet? He threatened to do so a few years ago after US immigration would allow him to pass through the US on his British passport (noticing his place of birth was NYC) with his family on the way to Mexico.

Instead he had to board a flight to Madrid and fly to Mexico that way. Nuts!

Petros they may in the future say that since you have not done FBAR, you are not tax compliant. Do not cross the border. Be wary of signing w8 ben especially if you have a substantial amount of money.