|

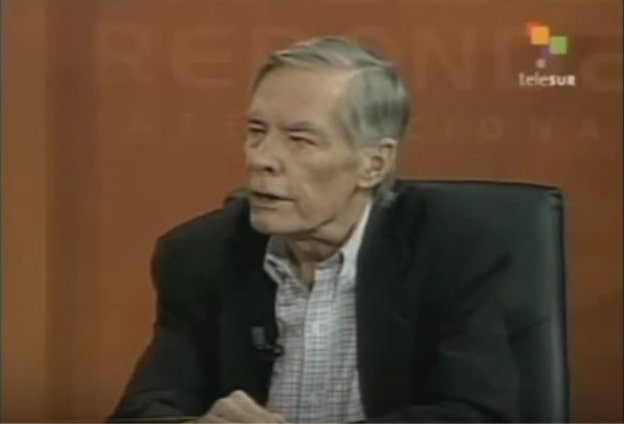

| Agee in a 2007 interview with TeleSUR’s Mesa Redonda in Cuba |

With all the attention suddenly being paid to China’s policy of forbidding Hong Kong dual citizens from using foreign passports to enter & leave mainland China unless they renounce Chinese citizenship (by mailing a form to the Hong Kong Immigration Department and paying US$19), it’s worth taking another look at the origins of the U.S. policy of forbidding U.S. dual citizens from using foreign passports to enter & leave the U.S. unless they renounce American citizenship (by waiting ten months for a consular appointment and paying US$2,350).

As mentioned last year, Ted Kennedy and Alan Simpson had to lie and obfuscate to get this policy made into law (8 USC § 1185(b)); prior to their change, it was legal for U.S. citizens to use foreign passports to enter and leave. Kennedy vaguely mentioned “technical challenges to application of the Travel Control Regulations by United States citizens who enter or leave the United States using foreign passports” as a reason for the ban, without explaining what he meant. One theory was that Kennedy & Simpson were aiming at the suddenly-increasing number of Americans naturalising in foreign countries — after losing various court cases in the 1980s to people who wanted to keep U.S. citizenship (e.g. Vance v. Terrazas, 444 U.S. 252 (1980); Kahane v. Shultz, 653 F. Supp 1486 (E.D.N.Y., 1987)), in 1990 the State Department adopted a new policy of assuming that Americans abroad intended to keep U.S. citizenship even if they committed relinquishing acts such as becoming a citizen of another country or working for its government.

But around the same time as Terrazas, another American abroad lost a case in the U.S. Supreme Court: Haig v. Agee, 453 U.S. 280 (1981). That case wasn’t about U.S. citizenship per se, but about the right to a U.S. passport. And it was not a victory for “rights of citizenship”: SCOTUS ruled that State could cancel the U.S. passport of ex-CIA employee Philip Agee. Agee remained abroad for some years, but by the late 1980s he was travelling in and out of the U.S. freely by entering through the Canadian border and then returning to Europe on a Nicaraguan travel document and later a German one (his wife Giselle Roberge was a dancer for the Hamburg Ballet).

Agee was, undoubtedly, the most high-profile U.S. citizen at the time who used non-U.S. travel documents to enter and leave the United States, and who thus would have been affected by Kennedy & Simpson’s new U.S. passport requirement. However, at the same time, other politicians were pushing to use passport revocation for enforcing child support orders — which might have made them notice that, under the law at the time, such revocation would be ineffective against dual citizens, who could get passports from other countries.

So in this post, we’ll look at the evidence: was Agee the specific person Kennedy & Simpson had in mind when they enacted the foreign passports ban? Why didn’t the government enact the ban earlier? And did this provision actually have any effect on Agee’s travels to the United States, by making him afraid he wouldn’t be able to leave again after he’d entered?