At the end of September, the IRS released preliminary figures for year 2014 filers of Form 3520-A, “Annual Return of Foreign Trust with a U.S. Grantor”, as part of the “foreign trusts” section of its Statistics of Income series. Many international accountants and tax lawyers take the position that ordinary local tax-compliant savings plans held by U.S. persons in other countries, such as Australian Superannuation, are “foreign grantor trusts” which generate the obligation for their “grantors” to file Form 3520-A as part of a complete compliance diet if the “trust” itself does not file the form.

This early IRS release breaks down “foreign trusts” only by extremely broad income categories — to give you some idea of what Homelanders think we owners of “foreign trusts” are like, the upper bound for the lowest category (aside from the category for trusts with a loss of any size) is US$0 to $100,000. For purposes of this blog post I’ll call this category “small reporting trusts” (though the category is defined in terms of income rather than trust assets). The final release will probably only break that down as far as $0–25,000.

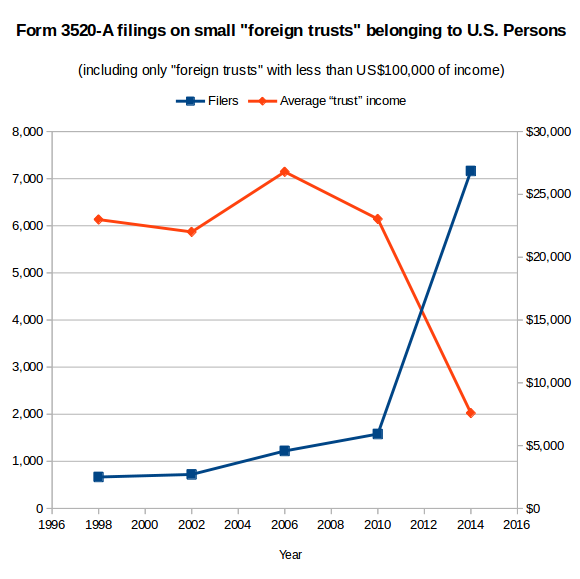

However, we can still see two related trends: many more “foreign trusts” with income under $100k are reporting, and on average they have far less income and less assets than “foreign trusts” which reported in previous years.

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1998 | 2002 | 2006 | 2010 | 2014 | |

| Trusts with $1 to $100,000 of income (“small foreign trusts”) | |||||

| Count | 667 | 772 | 1,220 | 1,580 | 7,163 |

| Average net income | $22,996 | $22,010 | $26,797 | $23,042 | $7,589 |

| Average assets minus liabilities | $910,425 | $2,002,040 | $1,411,437 | $1,389,438 | $389,986 |

| Estimated characteristics of newly-reporting “small foreign trusts” (Assuming that all trusts from previous period continued to report and had same net assets and income) |

|||||

| Count | +105 | +448 | +360 | +5,583 | |

| Average net income | $10,055 | $33,737 | $10,316 | $3,216 | |

| Average assets minus liabilities | $15,240,364 | $555,181 | $1,314,886 | $107,138 | |

Assuming that all the small reporting trusts from 2010 continued to report (not a perfect assumption — note the absurd result for average assets minus liabilities of trusts which began reporting during 1999–2002), that means the additional five thousand-plus small trusts which started reporting during 2011–2014 had an average of only ~US$3,200 of income and US$107k of assets. In fact, for the first time in the history of Form 3520-A, the average small reporting trust in 2014 had less income than an individual’s personal exemption plus standard deduction — i.e. even in those cases where the trust’s income is treated as belonging to its U.S. person “tax owner”, no U.S. tax is actually owed. (Note also that this analysis excludes trusts which had losses, since the IRS statistics lump together minnow “trusts” which had minnow-sized losses and whales with multi-million dollar tax losses which may or may not correspond to economic losses.)

I expect that precisely none of these new “small reporting trusts” are actual Panama Papers-style offshore trusts with a professional trustee taking legal title to some assets and then managing them for beneficiaries according to local trust law — the fees for those would eat up all the income. Rather, their size — about the same as the average U.S. 401(k) plan — strongly suggests that these are normal retirement accounts, not tax-evading drug-dealing money-laundering terrorist-financing instruments.

In simpler terms, after spending tens of millions on offshore compliance crusades, the IRS managed to dig up a bunch of local retirement plans which owe no U.S. tax.

Renunciants probably big portion of new 3520-A filers

Previous IRS efforts to improve the diaspora’s “tax compliance” have generated only mildly-less-dismal results. Between 2008 and 2012 the number of Forms 2555 filed by the diaspora increased by more than a hundred thousand, but the average income reported by each filer fell by an amount that suggested that the average new diaspora filers had pretty much the same income as average Homeland filers. As I stated back when those figures came out:

The average amount of FEIE has always been higher than the earned income on the average U.S. return. Homeland pundits often take this as confirmation of the stereotype of “wealthy expats getting great tax breaks”. However, the more likely explanation is that well-paid folks often have tax advice to match their wages (e.g. thanks to tax assistance provided as part of corporate international assignment packages) through which they learn of their U.S. filing requirements and hence show up in FEIE statistics, while people of more average means — whether expats in less high-flying jobs, or ordinary employees living in the countries they think of as home — don’t show up in FEIE statistics because they don’t know they have to file.

And awareness of Form 3520-A is clearly even lower: the number of Forms 3520-A being filed remains only a small fraction of the number of Forms 2555. (Even this growth seems to have caught the IRS by surprise: as recently as 2013, their Paperwork Reduction Act estimates stated that they expected only about five hundred 3520-As per year.) Does that mean that we should expect to see hundreds of thousands of new filers in the coming years?

The five thousand or so people who filed Form 3520-A on their retirement plans in 2014 are an unusual group: they are the 0.1% of the diaspora who try the hardest to comply fully with the U.S. tax system. How big a group is five thousand people? Well, the FBI added 2,426 more renunciants to NICS in 2014 than they did in 2010 (source: NICS Operation Reports — 2009 p. 19, 2010 p. 18, 2013 section “Active Records in the NICS Index”, and 2014 p. 25) — and recall that NICS doesn’t include relinquishers. I suspect that many of the new Form 3520-A filers were among the uptick in renunciants — and that these new filers only accepted the maximalist-extremist position that their retirement plans were “foreign grantor trusts” because their compliance condor told them it was a prerequisite to getting a CLN and officially exiting from the absurd system in as clean a fashion as humanly possible.

Some Homelanders love to repeat that out of the millions of Americans estimated to live in other countries, only a few thousand names show up each year in the Federal Register‘s list of ex-citizens — as if that’s an excuse for abusing the rest who don’t renounce. Yet comparing the number of Form 3520-A filers to the NICS renunciation figures suggests that something like half of people who try the hardest to comply fully with the U.S. tax system go and give up U.S. citizenship in the end. Either the burden of full compliance drives them to give up citizenship, or they are undertaking the burden only as a step along the way to giving up citizenship.

Executive can fix this problem without waiting for Congress

As far back as 2010, it should have been apparent to the IRS that their Form 3520-A filing requirements were netting them an enormous amount of by-catch. The by-country breakdown — not yet available for 2014 — showed that the largest increase in 3520-A filings between 2006 and 2010 came not any of the traditional trust-forming Commonwealth secrecy jurisdictions like the Cook Islands or Belize, but rather Mexico. There were 509 Form 3520-As filed for Mexican “foreign trusts” in in 2006, and 2,144 in 2010. Most likely, these “trusts” were fideicomisos — structures used by non-Mexican citizens to hold coastal land in Mexico. Since then, the IRS clarified to one tax filer in a Private Letter Ruling that they did not consider his/her fideicomiso to be a trust for U.S. tax purposes. Oh, and Canadian RRSPs are exempt from 3520-A filings too. Two tax jurisdictions solved, 190-something more to go!

In any case, Form 3520-A has a 43-hour record-keeping & form-filling time burden, according to Paperwork Reduction Act estimates. So the IRS wasted thirty thousand more eight-hour workdays of the diaspora’s time with this form in 2014, and if all of us bothered to comply with their incomprehensible and insane requirements, we’d waste millions of workdays every year. As we’ve pointed out before, it doesn’t have to be this way. 26 USC § 6048(d)(4):

The Secretary is authorized to suspend or modify any requirement of this section if the Secretary determines that the United States has no significant tax interest in obtaining the required information.

Trump says he’s going to kill a bunch of time-wasting regulations on Day One of his administration. So, are the Republicans going to keep their big promises to the diaspora?

Without action of the sort you suggest things will be getting worse with partial privatisation of pensions, attention to “Second Pillar” pension assets, and the new UK “Workplace Pensions” https://www.gov.uk/workplace-pensions-employers

Depending, of course, on interpretation by the IRS and practitioners. Trust rules and PFIC provisions have had insane results in the past as during the years that the UK Government gave free £250 “Child Trust Fund” coupons to every infant born or coming within the field of Child Benefit https://www.gov.uk/child-trust-funds/overview The accounting cost of compliance with the IRS over that Fund could easily exceed its value *each year*. The Junior ISA which replaced it could have similar burdens but at least it’s voluntary. (In principle the CTF couldn’t even be abandoned or disclaimed as there was a default provision; hence the link I gave has tracing advice.)

Leave them off or put them down as savings accounts.

@Iota….ahhh…Zen and the Art of FBAR.

@George – The CTF and Junior ISA are both exempt accounts under the IGA, so won’t be reportable by the FI. Unless the child (not the parent) has income sufficient to have to file a 1040, or has accounts over 10K, no requirement for the child to report. (I should coco!)

If the child has income/account levels sufficient to be required to report, and the parent considers it desirable to do so (why??), the obvious way to do it is to put the CTF and Junior ISA accounts down as savings accounts. It’s just common sense.

The problem with these forms is that there is a massive grey area on what should be filled. For example if superannuation plans have sufficient employer contributions that are supposed to be exempt from filling 3520. Some professions and lay people seem to want them filed for all. Since I am not Australian I have never dug into this case.

For the UK case we have ISA’s and pensions. Many people suggest ISA should have 3520 filed but there is no fiduciary and so they can’t be trusts. We chose not to file 3520 in OVDP and the IRS never asked for it. Likewise I have never filed this for my pensions. Of course never pensions in the UK can be these SIPPs and once again people want to say you need to file 3520 but again no fiduciary.

Obviously I won’t be filling this form or entering any program to file this form with penalties for my UK pensions. I’ll take the position that they can tax them only at withdraw.

@Neill, curious then what do you call an isa or sipp then it not a trust

A lot of things have become trusts because the compliance industry have made them into trusts.

Phil Hodgen had a blog entry about the isa here

http://hodgen.com/is-an-isa-a-foreign-trust/

I was lucky my Isa was below the filing requirement however I had a pension plan that had conflicting advise from accountants. Eventually I found a competent authority agreement that ended the debate. of course it was me that had to educate myself.

@George,

You can still call them a trust. It’s just the IRS definition requires a fiduciary. somebody has to manage the assets for you and be on the hook to do that job with your interests in mind. Self directed stuff doesn’t fit the bill.

@Eric

Great post as always. Interesting discussion going on about whether

certain kinds of retirement arrangements qualify as trusts to begin

with. If something is not a “trust” then it can’t be a “foreign trust”.

Also lots of discussion of Forms 3520 and 3520A.

A few points:

1. Form 3520A would apply only if one has a foreign GRANTOR trust.

Information about foreign GRANTOR trust is found Sections 671 – 679 of

the Internal Revenue Code. To be a GRANTOR trust this trust must have

been created by the taxpayer. The Internal Revenue Code description is:

26 U.S. Code Subpart E – Grantors and Others Treated as Substantial

Owners

found here:

https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/26/subtitle-A/chapter-1/subchapter-J/part-I/subpart-E

See also the directions for Form 3520A here which make it clear that it

applies to 671 – 679 trusts.

https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-pdf/i3520a.pdf

Bottom line: If no foreign “GRANTOR” trust then no 3520A.

2. Form 3520 is actually used for many purposes. These purposes relate

to both GRANTOR and NONGRANTOR trusts. It also is used to report gifts

from non-U.S. persons, etc. Before having a heart attack, take a moment

to peruse each section of Form 3520 to see if applies to you and the

directions for Form 3520.

https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-pdf/i3520.pdf

3. In most cases foreign pension plans are NOT GRANTOR (example the

basic Australian Superannuation) trusts. They were not created by the

U.S. person and nothing was transferred to them by the U.S. person. Now,

it’s possible that certain kinds of Australian Superannuations (example

direct “after tax” contribution from the employee) could be a GRANTOR

trust. But, in general not.

4. The fact that something is called a trust in Australia or Canada does

not make it a trust under U.S. law.

5. The compliance industry has a tendency to “over report” things as

Foreign trusts because they think they are protecting you from possible

penalties. They are NOT protecting you. They are creating problems for

you.

What you should be asking is this:

First, does it qualify as a “trust” at all under the principles of U.S.

trust laws?

Second, assuming it is a trust, is it a “foreign” trust. (See Internal

Revenue Code S. 7701)

Third, if it is a “foreign” trust, is it a “GRANTOR” (taxed directly to

grantor and not to the trust) trust or a “NONGRANTOR” trust (the trust

pays the tax).

Excellent comment Tricia – I was just sitting down to write up something similar.

With regard to Australian Superannuation – first – it’s not clear there’s really a trust to be reported, even though that’s what most compliance people do (and the IRS appears to be becoming more aggressive in this area). There are several theories out there about how to fit super into US tax law.

One theory is that super is equivalent to social security and therefore should be taxable only in Australia under the treaty. This theory will have even more support once the Superannuation (Objective) Bill 2016 is passed (this is currently in committee with a report expected in February). If superannuation is equivalent to social security, then it is not a trust that needs to be reported to the IRS. I’m not sure whether, under this theory, super is even a financial asset that needs to be reported on form 8938. I should note that there is disagreement as to whether ALL super is equivalent to social security, or only that portion of the account funded by concessional contributions, or only that portion of the account funded by required contributions. (yeah, it’s messy)

Another theory is that super is a non-qualified retirement plan for US tax. For the majority of Australians who do not make any extra contributions to their super, that non-qualified plan would probably be a 402(b) plan. Form 3520 specifically exempts 402(b) plans from filing.

There was a post on Facebook recently where an Australian resident (who apparently had not been reporting his super to the IRS) was asked by the IRS for both forms 3520 and 3520A. This person did not have a Self Managed Super Fund, though it was not clear whether non-concessional (after-tax) contributions had been made. Of course, the individual is trying to comply, but has no idea what the IRS is asking for. At one point in the thread he says “what is a trust?” Plus the IRS doesn’t really understand the Australian legal structures around super and are trying to force a square peg into a round hole. It’s a case of the blind leading the blind.

John Richardson left a comment on fixthetaxtreaty.org that is relevant here:

That’s only part of a much longer comment that is well worth reading.

Iota is right. Since no one knows what they are, leave them out.

@DoD

Unfortunately, we now have cases in Australia where the IRS is asking for these forms when they are not in the original return. While their request may not be correct, most taxpayers faced with an IRS request for a specific form will provide that form.

@DoD – I was referring to UK child savings accounts. I would leave out Child Trust Funds and Junior ISAs, because:

(a) on principle, because it’s a parent’s responsibility to protect the child, which IMO includes protecting them from ever coming to the attention of the IRS; and

(b) on common sense grounds, because most children’s savings accounts never reach levels that would require an FBAR or a 1040, so leaving them out is unlikely ever to trigger any flags in autoprocessing or lead to questions from the IRS.

Or, if the accounts are reported, they can easily just be put down as savings accounts, which indeed, it seems to me,mis what they are.

I would feel more cautious, when it comes to adult savings and pensions, as more money is involved and the risk of follow-up attention may be greater. A lot depends on individual circumstances. Personally I followed the well-established principle that one should tell them nothing they don’t already know, making sure one has an arguable case for all omissions. (Where “arguable case” includes “I thought that was the correct interpretation of these impossibly and deliberately vague, ambiguous, complex and confusing rules”)

No idea about Australian Superannuation. It sounds as if the IRS has a bee in their bonnet about this, which is so unfair.

@Neil, @Iota…..I hate this $%^& because when you think you have achieved nirvana you come across something and then you think your entire understanding falls apart, you turn into a jelly fish ready to start crying or screaming

OK, any and all…help me with this scenario. UK Citizen living in the UK who is deemed a US Citizen. I am going to give some income scenarios and write in caps whom I think according to treaty gets to tax, correct accordingly.

1. US Social Security. UK ONLY (Article 17, Section 3)

2. UK State Pension. UK ONLY (Article 17, Section 3)

3. US Government Service Pension (Article 19) (UK ONLY because the recipient is both resident and a national of the UK not simply a permanent resident. Article 19 Section 2b)

4. UK Employer Pension UK ONLY (Article 17, Section 2)

5. US IRA account. US ONLY (Article 17, Section 2)

**All the above are the exceptions to the citizenship not withstanding clause.

I would say the above is likely not the most overall tax efficient especially because US Social Security in the USA if your income is lower it is basically tax free.

@George – I agree with 1, 2, and 4.

With regard to 3….hmmmm….As I understand it, the US has primary taxing rights, so it would be the US who would need to concede under Article 19. But the Saving Clause says it will only concede if the recipient is neither a USC nor a PR. If the recipient is a USC, the US tax will presumably continue to be withheld.

HMRC and the IRS don’t always agree on what is or is not a government pension. Might be best to ask HMRC for a ruling.

Don’t know about IRAs.

Correction – I agree on 1 and 2. Number 4, the UK Employer Pension, would be taxable by both the UK and the US (i.e., FTCs would have to be claimed, possibly from the US via resourcing).

Article 17(2) only applies to lump sums and in any case, infuriatingly, is not an exception to the Saving Clause.

Dispiriting, but there it is.

@Iota, thanks for the input. I am trying to wrap my arms around Article 1 (5(b)) and how that relates to the savings clause in 4.

I think you understand it…..hence my question.

It looks very clear that everything in 5(a) is exempt from the savings clause.

The question is does 5(b) benefit US person at all? Or does 5(b) benefit US Persons everything before “and 28 (Diplomatic Agents……..”

So my question is does that end section after the comma solely affect the Diplomatic Agents and Consular Officer section or does it affect the full sub paragraph?

I think you may be reading ” , upon individuals who are neither citizens of, nor have been admitted for permanent residence in that State.” as negating the full sub paragraph.

Just when you think you had it all figured out…….. Looking at the UK/US treaty…….

I think I am about to transcend to the “Fifth Level of Understanding” having been at the lowly fourth level of understanding.

So if you are a UK/US Person resident in the UK then according to the treaty Savings Clause, the UK because you are resident can treat you as if the treaty did not exist and the US because of US indica can treat you as if the treaty did not exist except for the teeny tiny crumbs tossed about in subsection 5(a).

What a flippin sham.

@George –

I would parse Article 1(5)(b) thus:

“b) the benefits conferred by a Contracting State under:

{- paragraph 2 of Article 18 (Pension Schemes); and

– Articles 19 (Government Service), 20 (Students), 20A (Teachers), and 28 (Diplomatic Agents and Consular Officers) of this Convention,}

upon individuals who are neither citizens of, nor have been admitted for permanent residence in, that State.”

As I understand it, 1(5)(b) is specifically aimed at sparing those temporarily working in the US.

Relevant quote from an interesting article on US tax policy located at http://www.lexology.com/library/detail.aspx?g=3cae7b4e-dce0-4a84-9e3d-30f5dfb89194

(my bolding)

So I do think the US fully intends to retain its primary right to tax US Government pensions. But an even more salient point, for USCs abroad, is the fact that they’ve got the withholding power. To get the withholding removed, or claim a refund, the recipient would have to be able to get the US to accept that they should concede their primary taxing right. Article 1(5)(b) doesn’t seem to offer clear support for that argument.

@George – “So if you are a UK/US Person resident in the UK then according to the treaty Savings Clause, the UK because you are resident can treat you as if the treaty did not exist and the US because of US indica can treat you as if the treaty did not exist except for the teeny tiny crumbs tossed about in subsection 5(a).”

In theory. In practice, the Saving Clause tends to be used by the US, not the UK, since the UK is not trying to tax UKCs on the basis of citizenship. Also, the US cannot treat you as if the treaty didn’t exist purely on the basis of US indicia. It’s citizenship (or LPR-ness) that counts, although, unfairly, for FATCA purposes the onus is on the USP to prove innocence.

What a flippin sham.

@Iota…..as you likely know US short term expats and many US uni-citizen long term expats in the UK take rather dodgy positions with HMRC.

We know from the US UK treaty; “a Contracting State may tax its residents (as determined under Article 4 (Residence), and by reason of citizenship may tax its citizens, as if this Convention had not come into effect.”

OK, so a US/UK permanently resident in the UK can be treated by the US as if it did not exist and by the UK as if it did not exist……other than the crumbs in 5(a).

Here is what I have found at an official US Air Force website with advice to US retirees in the UK;

_____

Income Taxes on US Military Retirees’ Pay

Income taxes on U.S. military retirees’ pay: Money received as retirement pay by a retired U.S. military person resident in the United Kingdom is subject to income tax by the U.S. government, but such money is wholly exempt from tax by the British government.

Authority for this is the bilateral tax treaty between the U.S. government and the U.K. government. The current treaty came into effect on Jan. 1, 2004. For United Kingdom purposes, the treaty may be referred to as United Kingdom-3 Income Tax Treaty, and the relevant article is Article 19.

Should any bank or other financial institution attempt to impose British taxes on such money you should refer them to the provisions of this treaty. If a retired U.S. military person resident in the United Kingdom is required to file a British income tax return then the person’s military retired pay may be reported in the following manner. This procedure has worked without known exception.

On the supplementary pages for foreign income make no entry to the question about pensions income. In the additional information box at the end of the supplementary pages, enter the following: “Page F[number of page where question about pensions income is located], Pensions: Military Retirement Pay received from USA Government is not subject to UK tax–the provisions of Article 19, Section 2(A), of the United Kingdom-3 Income Tax Treaty apply.” Should you wish, you may add, “(For information only, the amount received was $…….)”.

Should you desire a copy of the treaty article, you may obtain it from the Internal Revenue Service, 24 Grosvenor Square, London W1A 1AE, England.

_________

What does that tell me? That tells me that part of the US Government is saying that Article 19 is not part of the savings clause.

Article 19 would not be part of the Savings Clause IF 5(b) did apply.

I think someone has problem here…agree?

@Iota, “In theory. In practice, the Saving Clause tends to be used by the US, not the UK, since the UK is not trying to tax UKCs on the basis of citizenship. ”

See immediately above where the right of HMRC to impose residency based taxation is being actively thwarted by the US Government.

@George – yes, the item on retired US military personnel confirms what I suggested above: the US will not concede its primary taxing rights. The UK will, and does, concede its secondary, residence-taxation rights. It’s completely in line with the Savings Clause.

“See immediately above where the right of HMRC to impose residency based taxation is being actively thwarted by the US Government.”

No – the US has primary taxing rights on US source income. Government pensions (including, apparently, military pensions) are taxable exclusively in the source country, by default. The UK isn’t being thwarted.

For comparison – I receive a UK Government pension, which is taxed by the UK as both source and residence country. I excluded it altogether when determining my US taxable income, because the US does not have taxing rights either as source country or as residence country, even though at the time I was a USC.

@Iota. “The UK will, and does, concede its secondary, residence-taxation rights.”

I agree from the treaty that the US can by the power of the purse tax those sums and let the beneficiary figure where to go from there.

But the USG is stating the money is wholly EXEMPT from UK tax from permanent UK residents. How can that be? This money should be declared to HMRC and a credit taken against tax paid to the USA. The USG is stating to not even declare it but to take a treaty position.

Where in the Treaty is the UK giving up its right to tax UK residents?

I am obviously missing something, your help is appreciated.

HMRC does not need to oblige on Article 19 towards its residents because of the savings clause with regards to residence. Are you saying that HMRC is agreeing to give up its power of residency taxation by following sections of the treaty that are in the savings clause with regards to residence?