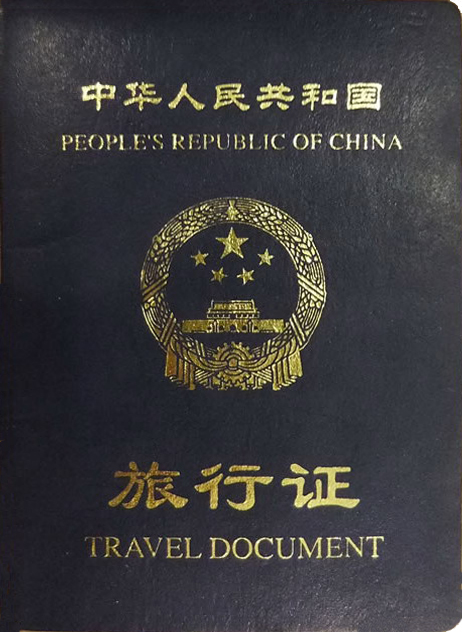

A couple of weeks ago, Chinese-language media in Canada reported that some second-generation Canadians with parents from Hong Kong have recently been unable to obtain visas for visiting mainland China, and were instructed by a visa processing centre to apply instead for temporary travel documents (pictured at right) as Chinese citizens instead. (Their right to visit Hong Kong is unaffected; Canadians can visit Hong Kong for up to 90 days, and the Hong Kong government does not require those with a potential claim to citizenship to resolve it before visiting.)

Nevertheless, these reports provoked a large number of inquiries to the Canadian government, and so the issue has leaked over into the English-language press just in time for the anniversaries of both the British North America Act 1867 and Hong Kong’s 1997 handover to China; various sources (CBC; South China Morning Post; Reuters; Time) are reporting the following fascinating statement by Felix Corriveau, a spokesman for Canadian Minister of Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship John McCallum:

Canada is aware of recent reports of challenges for Canadian-Chinese dual citizens in obtaining visas to visit China from Hong Kong. We are looking into the issue and are following up with the Chinese authorities.

Oddly, Messrs. Corriveau and McCallum do not seem to have sent any similar enquiries to Washington, D.C. regarding the far more aggressive policy of the United States towards Canadian individuals it claims to be U.S. citizens, which doesn’t simply include asserting sovereignty over alleged dual citizens when they visit the country and forbidding them from using foreign passports to enter, but rises to the level of threats to impose sanctions on Canada if Ottawa does not hand over their private information to Washington DC. An accidental oversight, I’m sure.

After the jump I translate portions of the relevant reports from the Canadian editions of Hong Kong newspapers Ming Pao and Sing Tao, and provide further discussion.

Table of contents

- Legal background

- The original Ming Pao report

- The Chinese government response

- Private sector overenforcement & misenforcement to blame?

- The Chinese nationality law and “one country, two systems”

- When the State meets someone who says he’s not a citizen

- Conclusion

Legal background

Visas and consular protection

Whether a dual-citizen tourist uses a Canadian passport with a Chinese visa, or a Chinese travel document instead, is relevant because of Article 12 of Canada & China’s 1999 Consular Agreement:

Facilitation of travel

1. The Contracting Parties agree to facilitate travel between the two States of a person who may have a claim simultaneously to the nationality of the People’s Republic of China and that of Canada. However, this does not imply that the People’s Republic of China recognizes dual nationality. Exit formalities and documentation of that person shall be handled in accordance with the law of the State in which that person customarily resides. Entry formalities and documentation shall be handled in accordance with the law of the State of destination.

2. If judicial or administrative proceedings prevent a national of the sending State from leaving the receiving State within the period of validity of his visa and documentation, that national shall not lose his right to consular access and protection by the sending State. That national shall be permitted to leave the receiving State without having to obtain additional documentation from the receiving State other than exit documentation as required under the law of the receiving State.

3. A national of the sending State entering the receiving State with valid travel documents of the sending State will, during the period for which his status has been accorded on a limited basis by visa or lawful visa-free entry, be considered as a national of the sending State by the appropriate authorities of the receiving State with a view to ensuring consular access and protection by the sending State.

This obliges China to ensure consular access by dual nationals who obtain visas or are allowed to enter visa free, but does not require China to issue those visas or otherwise let duals use their foreign passports in the first place; “facilitate travel” is sufficiently vague as to cover the current practice of issuing temporary travel documents to dual nationals or requiring them to use the special travel card given to Hong Kong and Macau residents.

Similarly, Corriveau stated that the 2015 China–Canada agreement on multiple entry visas does not require China to issue Chinese visas to dual citizens either; I haven’t been able to find a copy of the agreement myself to verify this, but it would be extremely unusual if it did have such a provision.

Nationality

So who is a citizen in the first place? China’s 1980 Nationality Law grants citizenship to some children born abroad (i.e. the second generation), but only if their parents have not “settled” in the foreign country. As the Hong Kong Immigration Department (“ImmD”) notes, “settled” is usually interpreted to mean that the parent is ordinarily resident abroad and is not subject to any limit of stay, which generally means permanent residence status. As far as nationality laws go, this is on the limited & conservative side; many countries claim the entire second generation as citizens regardless if they also have another citizenship, and some (most famously Italy) have no particular generational limit on the process.

| 第五條、父母雙方或一方為中國公民,本人出生在外國,具有中國國籍;但父母雙方或一方為中國公民並定居在外國,本人出生時即具有外國國籍的,不具有中國國籍。 | Article 5: A person born abroad shall have Chinese nationality if one parent is, or both parents are, Chinese citizens. However, if one parent is, or both parents are, Chinese citizens who have settled abroad, and the person acquired foreign nationality at the time of birth, then [the person] shall not have Chinese nationality. |

China’s policy since the mid-1950s has been to reduce cases of dual nationality and to push those who have dual nationality to choose one nationality as early as possible. They signed treaties with Indonesia and later Malaysia, the Philippines, and Thailand to this end, and legislated that acquisition of foreign citizenship would lead to automatic loss of Chinese citizenship.

However, Beijing made a rather large exception to this policy in the 1996 “Explanations” of how the Chinese nationality law would apply to Hong Kongers after the handover: they could have dual nationality and would not be required to pick one or the other (to save everyone the embarassment of large numbers of Hong Kongers picking a foreign nationality). The Explanations do not change how jus sanguinis applies to a person born abroad; they only change whether that person born abroad might subsequently lose Chinese citizenship. See for example TSE Patrick Yiu Hon v HKSAR Passports Appeal Board, CACV351/2001, at para. 11–13, confirming that a son of Hong Kongers, who was born in Germany and later naturalised there, had Chinese citizenship at birth and did not lose it by obtaining German citizenship.

Of course, there would have been no court case in the first place if Tse’s parents didn’t care that the government was trying to strip their son of his Chinese citizenship, and they probably celebrated or at least breathed a sigh of relief after they won. This illustrates the general principle we’ve mentioned before: case law on citizenship is almost always driven by people who want citizenship or want to keep it, and people who want out of citizenship may have a very different view on those “victories for the rights of citizenship”.

China’s history with the Master Nationality Rule

The Explanations also contain what’s effectively a municipal-law implementation of the Master Nationality Rule (as mentioned above, a few governments including Canada’s concluded consular agreements slightly modifying this rule with respect to their own nationals, though in practice these only protect those who didn’t live in Hong Kong, never had their right of residence confirmed after 1997, and visited exclusively using their foreign passports):

Chinese nationals of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region with right of abode in foreign countries may, for the purpose of travelling to other countries and territories, use the relevant documents issued by the foreign governments. However, they will not be entitled to consular protection in the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region and other parts of the People’s Republic of China on account of their holding the above mentioned documents.

It wasn’t surprising to see China assert the applicability of the Master Nationality Rule given the circumstances, but nevertheless it signalled their break with historical imperial & Republican practice.

Back in 1930, China (then the Republic of China, of which the People’s Republic of China is generally regarded as the successor state) participated in the League of Nations Conference that led to the Convention on Certain Questions Relating to the Conflict of Nationality Laws, but objected to the inclusion of the Master Nationality Rule in Article 4, and took until 1935 to ratify the convention — with a reservation against Article 4. The Kuomintang government of that era deeply resented the treatment of ethnic Chinese by colonial governments in Southeast Asia, and wanted to be able to offer them protection despite the fact that they (at least the locally-born ones) were also considered nationals by the colonial governments. (The nationality law China passed the year before the conference continued the Qing Dynasty principle of jus sanguinis without any generational limit for children born abroad, and did not make acquisition of foreign citizenship a ground for automatic loss of Chinese citizenship.)

The Communists came to power in China around the same time as decolonisation in Southeast Asia, and as mentioned above they sidestepped the issue of consular protection and the Master Nationality Rule by focusing on efforts to minimise dual nationality. However, the dual nationality issue came up again in the 1990s with the impending return of Hong Kong, and ironically that led to a complete turn of the tables: now we see the Anglosphere countries implicitly rejecting the Master Nationality Rule (witness Britain’s complaints of being denied consular access to dual citizen Lee Bo earlier this year) while China asserts its continued validity.

The original Ming Pao report

The original report on visa denials a couple of weeks ago in the Western Canada edition of Ming Pao was a bit confusing. It noted both an allegedly-new policy of denying Chinese visas to Canadian citizens born in Hong Kong, and a case in which two people born in Canada were apparently identified (misidentified?) as Chinese citizens and were thus instructed to obtain Chinese temporary travel documents rather than visas.

因父母是香港出生加籍人 土生青年被拒辦中國簽證 |

Two local-born youths denied Chinese visas because parents are Canadian citizens born in Hong Kong |

| 6月2日起實施針對加籍香港人簽證新例 | New visa rule targeting Hong Kongers with Canadian citizenship since 2 June |

| http://www.mingpaocanada.com/Van/htm/News/20160619/vaa1h_r.htm | |

| 由6月2日起,凡香港出生的加籍人士,都不獲中國簽發10年旅遊簽證,除非該人之前已曾獲發該簽證。 | Since 2 June, Canadian nationals born in Hong Kong have been unable to obtain 10-year Chinese tourist visas, unless they have already been issued a visa previously. |

| 新辦法推出之前並無預告,到目前為止,亦未有任何官方機構出面解釋原因,亦無指示此等加籍港人若要往中國時,應申請何種證件。 | There was no advance warning before the new policy was rolled out, and up to now there has been no official explanation of the reasons, nor any instructions on what type of documents Hong Kongers with Canadian citizenship should seek to obtain when going to China. |

| 有代辦中國簽證的旅行社表示,最少兩名在本地出生的青少年,因其父母是香港出生的加籍港人而被中國簽證服務中心拒絕辦理中國簽證。 | A tourism company which handles Chinese visa applications stated, at least two youths born in Canada were refused visas by the Chinese visa processing centre because their parents were Canadian citizens born in Hong Kong. |

| 旅遊業人士說,由於事前未有任何通知,很多旅行團的行程受到影響。一些在6月2日後成團的中國旅行團,因團中一些加籍港人拿不到中國旅遊簽證,被逼退團。 | A person in the tourism industry stated, because there was no advance notice, many tour groups’ itineraries have been affected. Some tour groups which had planned to travel after 2 June have seen Hong Kongers with Canadian citizenship who were unable to obtain Chinese tourist visas and were thus forced to withdraw from the tour group. |

| 以那兩名被拒申請簽證的本地出生青年為例,他們原本參加了一個40人的暑期中國遊學團,但現時不被接納申請,簽證中心又沒有明確指示應申請何種證件,只含糊的說要去總領事館申請「旅行証」,但手續如何、要具備何種證件就沒有說清楚。 | For example, the two local-born youths who were refused visas originally planned to join a 40-person summer study tour to China, but at the moment their applications have not been accepted. The visa centre did not explain what kind of documents they should apply for, and only vaguely told them to go to the consulate to apply for “travel documents”, but did not tell them about the procedures or what kind of documents they would need to obtain. |

| 據悉,該兩名青年在多倫多出生,他們由旅行社代辦簽證時,簽證服務中心要求兩人提供出生證明。當兩人提交本地出生證書後,中心發現兩人的父母是香港出生的,於是拒絕接受兩人的申請。至於因何父母在香港出生的「土生」人士會不能獲發中國簽證,中心並無解釋,只着兩人往總領事館申請「旅行証」。 | It is understood that the two youths were born in Toronto, and when they approached the travel agency to apply for visas, the visa processing centre asked them to provide birth certificates. After they provided their local birth certificates, the centre discovered that the parents of the two were born in Hong Kong, and rejected their visa applications. With regards to the reason that local-born people with parents born in Hong Kong could not obtain Chinese visas, the centre did not explain, and just left the two to go to the consulate to apply for travel documents. |

| 至於現時在港出生的加籍港人不獲簽證的做法,旅行社也是6月2日後才陸續知道。由於並無任何正式公布,目前只知受影響的,都是以前從未取得過中國簽證的香港出生加籍香港人,在香港以外出生、包括澳門及中國在內的人士則不受影響。 | It was only after 2 June that the travel agency gradually learned of the current practice of not issuing visas to Hong Kongers with Canadian citizenship. Because there was no formal announcement, at present it’s only known that those who have been affected are all Hong Kongers with Canadian citizenship born in Hong Kong who had never previously obtained Chinese visas. Those born outside of Hong Kong, including in Macau or mainland China, have not been affected. |

| 曾有人問過,這類受影響的香港加籍人士前往中國時,應申辦何種旅遊證件?他們被告知要親自前往中國駐當地總領事館申辦有效期兩年的「旅行証」。 | Some people have asked, if those Hong Kong Canadian citizens who have been affected plan to go to China, what kind of travel document should they apply for? They’ve been told that they should go to the local Chinese consulate in person to apply for a two-year travel document. |

In response to reports like this, the NDP’s Jenny Kwan, who was born in Hong Kong, said:

“The change in practice should be of grave concern to Canadians, after all, a Canadian is a Canadian. As such, should all Canadians not be treated the same?”

Unfortunately, neither Ming Pao nor Sing Tao showed much attachment to that idea. The simple unadorned term “Canadians” (加拿大人) appears nowhere in any of the Sing Tao articles, and only once in another Ming Pao article in reference to Canadian-born children who did not have any claim to Chinese citizenship. For the most part, they called the individuals affected by the visa policy, including those born in Canada, “Canadian citizen Hong Kongers” (加籍香港人) or, less often, “Hong Kong Canadian citizens” (香港加籍人, which could also be translated “people with Canadian citizenship in Hong Kong” depending on how you want to spin it).

The Chinese government response

Rival paper Sing Tao did a series of follow-ups two days later, which called into question the basis for the Ming Pao reports. The longest article was devoted to their interview with Shen Qisong of the Chinese Consulate in Vancouver, who denied that there was any new policy, and made two observations on the application of Chinese nationality law to Hong Kongers and their descendants.

First, Shen stated that people born in Hong Kong who had not made a declaration of change of nationality to the Hong Kong government would continue to be treated as Chinese citizens, regardless of whether they had obtained another citizenship, and the Chinese government would not issue visas to Chinese citizens for travel to mainland China. Second, he explained that children born in Canada to parents who had not yet obtained Canadian permanent resident status would be regarded as Chinese citizens under the Chinese nationality law, and thus when second-generation Canadians of Hong Kong background apply for Chinese visas, they would sometimes need to provide additional information so that the consulate could determine whether they were foreigners (and could thus obtain visas) or Chinese citizens (who should thus obtain travel documents).

Ministry of Foreign Affairs spokesman Hong Lei also fielded a question about this topic during a press conference in Beijing on Wednesday, and responded in a similar fashion as Shen:

Q: Reports say that Chinese authorities are no longer allowing Canadian citizens born in Hong Kong to visit China on 10-year visas. Is that true?

A: First and foremost, in accordance with the visa reciprocity arrangement reached by the Chinese Foreign Ministry and the Canadian Embassy in China on February 28, 2015, the two sides would issue multi-entry visas with the validity of up to ten years and within the term of validity of the passports to each other’s citizens coming for the purposes of business, tourism and family-visit, starting from March 9, 2015. China has been acting in strict accordance with the reciprocity arrangement.

Second, with regard to the issue of visas, travel documents and passports by Chinese diplomatic missions in Canada to Chinese citizens from Hong Kong living in Canada, reports about China making adjustment to or tightening its policy are not true. We handle visas, travel documents and passports applications by Chinese citizens from Hong Kong in accordance with the Basic Law of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of the People’s Republic of China (PRC), the Nationality Law of the PRC and the Interpretation by the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress on Some Questions Concerning Implementation of the Nationality Law of the PRC in the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of the PRC. As for what will be granted in the end, it is based on the personal information about the applicant and related documents.

Sing Tao also interviewed immigration lawyer Chan Lu of Burnaby, who confirmed that those who entered China on Chinese travel documents rather than Canadian passports would not be entitled to consular protection. That article also noted that about 4,400 Hong Kongers had made declarations of change of nationality to ImmD since 1997, thus effectively giving up Chinese citizenship (and allowing them to apply for visas to travel to mainland China using their foreign passports).

Private sector overenforcement & misenforcement to blame?

Beneath all the fancy ministerial rhetoric is a familiar problem: the Chinese consulates in Canada appear to have outsourced visa processing — and thus de facto nationality determinations — to a private-sector firm whose main concern is to take as little risk as possible so they can keep the contract dollars rolling in and can’t be accused of doing things wrong. Interestingly, in some cases that ends up pushing applicants to tell lies so they can fit into pre-defined categories more neatly. As Ming Pao reported in another article:

| 這位人士說,他了解申請簽證的手續會是很複雜,也常會改變,但自從簽證工作由簽證服務中心負責後,服務水準實在不敢恭維。 | This [travel industry source] said, he understood that the procedures for applying for a visa are complicated, and often change, but ever since the visa service centre took responsibility for visa processing, the level of service really has not been praiseworthy. |

| 他指出,簽證服務中心很多時都不會靈活處理問題,鐵板一塊,也不告訴你應該怎樣辦才對,就如現在加籍香港人不能申請簽證,中心除了拒絕申請外,不會告訴你如何去申請「旅行証」。他曾替一位客人辦證,對方如實填寫赴華原因是到深圳大鵬灣掃墓,國內並無親友,但簽證中心堅持要對方出示國內邀請函,否則不接受。結果這人後來改為深圳一日遊,並由旅行社出具證明才拿到簽證。 | He pointed out, the visa service centre is often absurdly inflexible in handling problems, and does not tell you how to do things correctly. For example, Hong Kongers with Canadian citizenship now can’t apply for visas, but the centre not only rejects applications, it doesn’t tell you how to apply for a travel document either. He brought up the example of one customer he helped to apply for a visa, who truthfully wrote on the application form that he was to go to Dapeng Bay in Shenzhen to visit an ancestor’s grave, and that he had no friends or relatives in China, but the visa centre insisted that he provide an invitation letter or they would not accept his application. In the end, the person was only able to obtain a visa after changing his reason to one-day tourism in Shenzhen and obtaining proof from the travel agency. |

And of course, there have already been errors in the other direction anyway. Another short article in Sing Tao featured an interview with a Mrs. Chan in Vancouver who said that she’d been able to get 10-year Chinese visas for all her family members, including her Canadian-born son, even though she was born in Hong Kong and never made a declaration of change of nationality to the Hong Kong government, and even though the Vancouver consulate is believed to be stricter than Toronto in processing visas.

The Chinese nationality law and “one country, two systems”

Divided responsibility for visas & nationality

Reuters stated about the visa policy change:

If true, the changes could be seen as an encroachment on Hong Kong’s autonomy. Hong Kong has been governed as a special administrative region since its return to China from British rule in 1997, a policy known as “one country, two systems.”

Casey Quackenbush, an American journalist in Hong Kong writing for U.S. magazine Time, editorialised that into:

If confirmed, the requirement would be another breach of the high degree of autonomy promised to Hong Kong by Beijing when China resumed sovereignty of the former British colony in 1997.

Under “one country, two systems”, Beijing does not control Hong Kong visa policy. The Hong Kong government has always been happy to let Hong Kongers and their children who have not applied for verification of eligibility for permanent residence after 1997 to visit Hong Kong on their foreign passports (thus usually making them entitled to foreign consular protection under the relevant agreement, even if they might also have a claim to Chinese citizenship). There is no evidence that this policy has changed. Nor would it be practical to do so: the vast majority of Hong Kong emigrants moved to countries which enjoy visa-free travel to Hong Kong, and so do not need to apply for advance visas.

But as it should also go without saying, Hong Kong does not control mainland China’s visa policy either. Beijing, for whatever reason, has decided that dual citizens from Hong Kong should not be allowed to visit on foreign passports. Other sovereign countries — including the United States — have made that same decision, and as discussed below, it’s hard to argue that China’s policy in this regard is unreasonable (whatever you might think of all their other policies): if you’re a Hong Kong Chinese & Canadian dual citizen and want to stop being dual so you can visit China on your Canadian passport, your path out of Chinese citizenship involves mailing a form to Hong Kong and paying a small processing fee (two digits Canadian, not four digits), and you don’t even have to give up the right to move to Hong Kong in the future.

Practical implementation

Under the Explanations, the Hong Kong Immigration Department (“ImmD”) has the authority to handle nationality applications from Hong Kong residents. In practical terms, this means that someone born overseas to a Hong Kong parent can go to Immigration Tower in Wanchai and try applying for a Hong Kong identity card, and during the process, ImmD will decide whether or not the person is a Chinese citizen (and also whether or not the person actually has residence rights in Hong Kong, which is a somewhat orthogonal question — particularly for people born before 1997), and once they’ve decided, the national government (i.e. Beijing) has no right to override that decision.

(The reverse question — whether Hong Kong could override Beijing’s determination of the nationality of a Hong Kong resident — doesn’t seem to have a clear answer. The Court of First Instance certainly asserted that right when the above mentioned Tse Yiu Hon case came before them — see HCAL 1240/2000, at para. 81. The Court of Appeal allowed an appeal from the Court of First Instance’s ruling, but didn’t say anything at all about this particular point.)

So what if someone has never gone to Hong Kong ImmD before, and instead the person goes straight to a representative of the Chinese national government in Canada and asks for a service — visa issuance — which presupposes that the person is a foreigner? Perhaps you could read the “one country, two systems” principle to require that Beijing proactively forward to Hong Kong ImmD all cases of people abroad who might be Chinese citizens by virtue of their connection to Hong Kong. But that would result in extreme delays in visa processing and even more complaints than the current setup, and would not give significantly different answers to the main question of whether or not the applicant is a Chinese citizen.

When the State meets someone who says he’s not a citizen

General principles

So let’s accept for the moment that if someone shows up at a Chinese consulate, the consulate should be the one to make a decision on his nationality. And also, as mentioned above, the Chinese government does not want dual citizens visiting on their foreign passports, and in general wants to minimise dual citizenship because of the issues it causes. So should the Chinese national government’s response to a visa application by a potential Chinese citizen be to strip that person of Chinese citizenship automatically?

Many Canadians might laugh at the phrase “benefits of Chinese citizenship”. But at the same time, it’s clear that many would also enjoy the opportunity to study or work in Hong Kong for a few years. We have 300,000 Canadian citizens here, and according to Sing Tao 85% of them were actually born in Canada (rather than being reverse migrants who were born in Hong Kong, went to Canada, and then came back after naturalising). And after 1997, the ability of a person born overseas to claim right of abode in Hong Kong is tied to whether or not the person acquired Chinese citizenship at birth; if they didn’t, then they’ll need a visa to come live here. Furthermore, if you do decide to live in Hong Kong, you’ll enjoy both professional and personal advantages if you can visit mainland China without needing to applying for a visa. These are two concrete “benefits of Chinese citizenship” which many people would be interested to know they had inherited. They come with drawbacks, but they are benefits nonetheless. And most importantly, the drawbacks are co-extensive with the benefits; they don’t have any implication for your ordinary life in Canada, and will only affect you if you go to Hong Kong or mainland China.

Different people will have different assessments of whether the benefits are worth the drawbacks. Either way, the first principle for a government dealing with people abroad who might have a claim to its citizenship should be to avoid turning ordinary interactions into a game of “gotcha!” — either by telling people who might have been citizens that they destroyed their claim to citizenship by filling out a visa form, or by telling people who might have been non-citizens that they are now trapped in citizenship, subject to severe penalties for failing to fulfill its duties because they or their parents carelessly asserted one of its rights, and now must traverse more than a year of bureaucracy if they “changed their mind” about wanting that citizenship.

Dublin comes to my mind as an example of a government that’s done this the right way, with respect for the choice of the individual. (Parts of that are attributable to the Good Friday Agreement, but others reflect long-standing warm feelings towards the diaspora, as well as a reasonable stance on renunciation.) Some people are entitled to be Irish citizens. They can continue to act as foreigners in relation to the Irish government if they wish. Later on they can assert Irish citizenship by doing an act that only an Irish citizen can legally do, like applying for an Irish passport. And Irish citizens can make a declaration of alienage, apparently without paying a fee; government statistics show a few dozen people doing so each year.

The path out of citizenship

In theory, it might seem like a big difference whether a person is deemed a citizen without his knowledge and consent, or is instead only deemed a citizen when he explicitly notifies the government that he’s accepting citizenship (indeed, this is one of the things that Dublin changed after the Good Friday Agreement). This difference is often attributable to statute, treaty, or even the constitution, and can’t be easily changed by the executive. However, the difference can be minimised by administrative practice: the government can warn the person of his unexpected citizenship status at the earliest opportunity, and give him a reasonable opportunity to make a choice about whether he wants to keep it before they come after him with demands to fulfill its duties.

And this is more or less what the Chinese government is doing. Various incidents going at least as far back as the arrest of Ching Cheong more than a decade ago have renewed Hong Kongers’ concerns about whether they can get foreign consular protection while traveling in mainland China. Well, being told that you’re a Chinese citizen before you travel to China — i.e. when they reject your visa application and tell you to get a travel document instead — puts you on notice that you don’t get consular protection. That’s far superior to the earlier situation where a potential dual citizen might be issued a visa without any clear answer about whether he’s a citizen, but could lose consular protection if he accidentally overstayed.

Furthermore, those who have Chinese citizenship and don’t want it are not trapped in it, contrary to Jenny Kwan’s claim (reported by CBC) that “this could potentially prevent thousands of Hong Kong-born Canadians from travelling”. As Sing Tao‘s interviewees pointed out, accidental Chinese citizens of Hong Kong background can make a declaration of change of nationality to the Hong Kong Immigration Department. You can send in the required form by post, and ImmD’s annual report for 2014 states that confirmation letters of declaration of change of nationality were issued to 100% of applicants on the same day for a fee of less than US$20.

The consequences of choosing non-citizenship

Hong Kongers who give up Chinese citizenship suffer few consequences for exercising the human right to change nationalities. Though they have to obtain visas for traveling to mainland China in the future and could theoretically be denied such visas, mainland China was never their home in the first place. They are not threatened with exile from their home or their parents’ home, no matter what they say about their reasons for giving up Chinese citizenship: they retain the right to live and work in Hong Kong regardless of their Chinese citizenship, though they lose the right to take up high-level Hong Kong government jobs and a few other odd things, and might lose the right to vote if they have been away from Hong Kong for a long time (though they can regain it after seven years’ residence). They still get a Hong Kong ID card and can still use the fast immigration lane at the airport.

(I almost wrote that there are no tax consequences for Hong Kongers who give up Chinese citizenship, but this is not strictly true: if a person has the right of abode in Hong Kong but is downgraded to right to land after giving up Chinese citizenship — which happens if they have not previously lived here for seven years — then they are subject — like all people who lack the right of abode — to buyer’s stamp duty if they want to buy property in Hong Kong. However, this appears to be an accidental interaction of various laws, not a deliberate policy to penalise changes of citizenship. It has no effect whatsoever on permanent emigrants who don’t live here, and there are no nasty legislative demagogues snarling that people who buy a flat before giving up Chinese citizenship are “tax cheats” who should be banned from Hong Kong.)

Conclusion

It is reasonably easy for Canadians of Hong Kong background with accidental Chinese citizenship to give it up under Chinese law so they can enjoy the full protection of Canada while traveling in the “old country”. Even if the Chinese government deems that they accepted & kept that accidental Chinese citizenship because they never renounced it, if they remain in Canada and avoid traveling to China it imposes no consequences on them in Canada — and there would be public outrage if the Canadian government accepted that it should impose consequences.

In contrast, Canadians with clinging U.S. nationality who want to give it up under the U.S. State Department’s rules face a procedure which is at minimum more than a hundred times as expensive and more than a hundred times as long (not even counting the cost of tax filings, the expense of the required in-person trip to the consulate, or the time spent waiting for a CLN). And as long as they have not completed that procedure the Canadian government has decided (both by signing treaties and by passing domestic legislation) that they should have numerous disabilities imposed on them.

Yet Canada’s Immigration Minister is publicly taking Beijing to task over the situation of Canadians of Hong Kong background, while remaining silent to Washington, D.C. about the situation of Canadians of American background.

Quite apart from the US jus sanguinis issues, the Chinese position on certain members of its diaspora is extremely significant. For many years China had no nationality law (Israel likewise didn’t, for a while). It avoided making allegiance claims on its diaspora for fear of worsening the hostility against ethnic Chinese throughout Asia. And of course in the USA there was the Chinese Exclusion Act https://networks.h-net.org/node/16794/reviews/16855/dong-salyer-laws-harsh-tigers-chinese-immigrants-and-shaping-modern

But it seems China is getting bolder in asserting claims to international waters, other countries’ exclusive economic zones, and reefs all over.

Countries for now are unafraid to push back against Chinese exorbitance. Few dare do so against the USA, which uses its sovereign power to extort compliance. Up to a point: it remains to be seen how those who may or may not have US status and who choose to defy are protected by foreign courts and governmental agencies. Especially at a time when the USG is seeking wider provision for mutual enforcement of tax claims (at least where the target is a non-citizen of the country of residence) and extradition (at least where tax evasion can be assimilated to money laundering and … terrorism).

If a country is not willing to “push back” against “US exorbitance” then should perhaps it should offer to simply surrender the country to the United States. This would avoid the difficulties of the gradual U.S. colonization of the county by claiming their people as U.S. citizens (one FATCA year at a time), deeming investment products to be PFICs (one retirement vehicle at a time) and conferring “foreign corporation status” (one professional corporation at a time) on small businesses. This way the country would be completely subject to U.S. law and there would no “foreigness” left for the USA to penalize.

Judging from the behavior of Canada’s Parliament in their celebration of the arrival of Barack Obama, I am inclined to think that Justin should make it official, call Obama and say:

Eric: Thank you for sharing this excellent piece of in-depth research, once again. It is yet another example of how the community of US-born Canadians is being singled out for “exceptional treatment” by the government that is supposed to support us, as it is supporting these Chinese-Canadians.

http://www.scmp.com/news/hong-kong/politics/article/2003353/canada-guarantees-full-consular-services-dual-national

@Eric “Responding to public alarm….”

Here we learn a key motivation for having McCallum get tough with a country (say, the the U.S.).

Or maybe all we learn is it’s easy for him to to grandstand when it’s China.

“Responding to public alarm….” Really? Smell that home cooking in McCallum’s PR department.

https://www.thestar.com/news/immigration/2016/08/18/ottawas-new-air-travel-rule-catches-dual-citizens-by-surprise.html

More: http://notable.ca/dual-citizens-must-have-a-canadian-passport-to-re-enter-canada-by-air-starting-next-month/