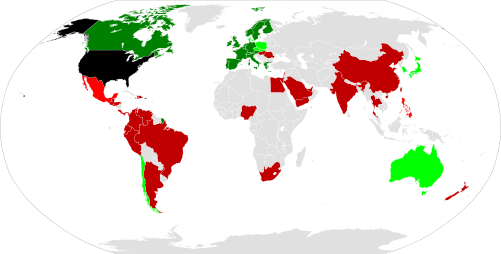

| Sources of data: Social Security Administration, U.S. State Department via American Citizens Abroad | |||

| United States | |||

| Totalization agreement in force by 1978–1999 | No agreement, 100,000+ U.S. citizens in 1999 | ||

| Totalization agreement in force by 2000–2014 | No agreement, 10,000+ U.S. citizens in 1999 | ||

In 1999, among the estimated 4.2 million U.S. citizens residing outside of the U.S., 1.7 million lived in countries which had Totalization Agreements with the U.S. at the time, while 280,000 lived in countries for which Totalization Agreements with the U.S. would come into effect by 2014. The remaining 2.2 million lived in countries where they would have to pay U.S. Social Security taxes on top of any similar local taxes if they worked for U.S. companies or for themselves — without any credits to prevent double taxation.

Table of contents

- Social Security and Totalization Agreements

- Self-employment

- Tom Coburn’s “solution”

- Conflict with domestic policy goals

- Underestimates of effects on the diaspora

- The connection to FATCA

- Conclusion

Social Security and Totalization Agreements

The U.S.’ Section 901 Foreign Tax Credit only covers income taxes. If you pay a non-U.S. tax which is not an income tax, you cannot apply it as a credit against any U.S. taxes you owe. And even if you pay a non-U.S. tax which is an income tax and have excess FTCs left over after applying those taxes as a credit against your U.S. income tax bill, you cannot use the remainder to reduce the non-income taxes you pay to Washington.

Aside from consumption taxes, social security taxes are the other major kind of non-income tax which most people face. As the Social Security Administration points out:

Dual Social Security tax liability is a widespread problem for U.S. multinational companies and their employees because the U.S. Social Security program covers expatriate workers–those coming to the United States and those going abroad–to a greater extent than the programs of most other countries. U.S. Social Security extends to American citizens and U.S. resident aliens employed abroad by American employers without regard to the duration of an employee’s foreign assignment, and even if the employee has been hired abroad. This extraterritorial U.S. coverage frequently results in dual tax liability for the employer and employee since most countries, as a rule, impose Social Security contributions on anyone working in their territory …

As one can readily see, the employee’s foreign Social Security coverage results in a substantially greater tax burden for the employer than the nominal Social Security tax alone. Depending on the other country’s tax rates, in some countries this “pyramid” effect has been known to increase an employer’s foreign Social Security costs to as much as 65-70 percent of the employee’s salary, as illustrated below.

Totalization Agreements, which solve this double-taxation problem, are separate from income tax treaties. Unfortunately, as the map above illustrates, the U.S. network of agreements is quite narrow — it covers most of the European Union, but only two countries in Asia and one in Latin America. Furthermore, even if you pay double social security taxes, you certainly don’t get twice the benefits, due to the Windfall Elimination Provision.

Oddly enough, for U.S. Social Security purposes, “employment” only means employment by a U.S. employer and not a non-U.S. employer (distinct from how income tax works). This means that American emigrants only face double social security taxation if they work for U.S. employers.

Self-employment

Unfortunately, if you emigrate and work for yourself, you’re still defined as working for a U.S. employer. Again from the Social Security Administration:

U.S. Social Security coverage extends to self-employed U.S. citizens and residents whether their work is performed in the United States or another country. As a result, when they work outside the United States, citizens and residents are almost always dually covered since the host country will normally cover them also. Most U.S. agreements eliminate dual coverage of self-employment by assigning coverage to the worker’s country of residence. For example, under the U.S.-Swedish agreement, a dually covered self-employed U.S. citizen living in Sweden is covered only by the Swedish system and is excluded from U.S. coverage.

As Phil Hodgen has recently discussed in great detail, there is a “simple” way to avoid this kind of taxation: form a corporation where you live (it has to be a non-U.S. corporation, since otherwise it’s a U.S. employer for Social Security purposes). Unfortunately, then you’re a Controlled Foreign Corporation owner for IRS purposes and you waste all your Social Security tax savings on accountants’ fees — which obviously don’t count towards your forty qualifying quarters for Social Security coverage — to help you fill out the execrable Form 5471.

As the IRS’ own estimates state, Form 5471 (including Schedule M, which as a 100% owner you would be required to file every year) imposes a 115-hour annual record-keeping burden, plus another 25 hours to fill out the form. Quite obviously, there are economies of scale here — Google spends proportionally less of its total employee time on record-keeping than a one-person corporation. Or to put it another way, the U.S. tax system imposes a regressive burden on self-employed American emigrants, whether they choose double social security taxation or insane form-filling.

Tom Coburn’s “solution”

Almost no Homeland politicians have noticed this disincentive for American emigrants to work for U.S. companies or for themselves; one of the few who has is Tom Coburn (R-OK), a mercantilist who thinks that Americans working for non-U.S. companies are traitors and saboteurs of American competitiveness, and apparently the “solution” he has in mind — on top of eliminating the Foreign Earned Income Exclusion — is to try to impose Social Security taxation on American emigrants working for non-U.S. companies as well. As he stated in his Back in Black: Reforming Tax Expenditures and Ending Special Interest Giveaways tax plan (at p. 35):

Regardless of where they live, U.S. citizens with identical incomes should have similar tax liabilities. The Congressional Research Service also found this provision is potentially a subsidy for business because it “subsidizes employers sending employees overseas” and it “may work against U.S. domestic interests by encouraging highly compensated U.S. citizens to work overseas … expatriating U.S. intellectual capital and reducing U.S. tax revenue.”

Also of note, citizens working overseas are not just working for American companies. In the 21st century global economy, many Americans are working overseas for non-U.S. companies, yet taking advantage of this tax break. The tax exemption is provided for these employees, but is not necessarily encouraging U.S. competitiveness. In fact, depending on the country, some employees working for non-U.S. companies may not be subject to Medicare and Social Security taxes, in addition to enjoying the income tax exclusion.

Conflict with domestic policy goals

Other countries unilaterally exempt long-term emigrants from participation in the social security system of their “old country”; thus their totalisation agreements can instead focus on the issues of double non-coverage (where a person moves from one country to another in mid-career, and ends up qualifying for neither’s benefits) and short-term expatriates who generally prefer accruing benefits in their home country systems. However, thanks to the U.S. insistence on taxing non-resident citizens in addition to residents of all nationalities, U.S. Totalization Agreements have to address the issues of all three groups.

The U.S. treats each Totalization Agreement as an executive agreement, even when the partner country regards it as a treaty and puts it through its normal parliamentary ratification process. However — much unlike FATCA Intergovernmental Agreements — there is at least specific statutory authority (Section 317 of the Social Security Amendments of 1977) for the executive to sign Totalization Agreements. Under that law, Congress does not have to ratify a Totalization Agreement for it to come into effect, but the President must at least inform Congress, and either chamber can prevent the agreement from coming into effect by a resolution of disapproval, though only for a limited period of time after they’ve been informed of the agreement.

Beginning in 2005, Republicans began sponsoring several bills — H.R. 2339 that year, H.R. 279 and S. 43 in 2007, H.R. 132 and S. 42 in 2009, S. 181 in 2011, S. 767 in 2013 — to require ratification of Totalization Agreements by both houses of Congress. The trigger for this sudden Congressional interest: the June 2004 announcement that Bush the Lesser had reached a Totalization Agreement with Mexico. If it had come into effect, it would have been the second U.S. Totalization Agreement with a Latin American country, following the 2001 agreement with Chile.

Emigrants’ concerns played precisely no role in the Homeland’s debate over the Mexican agreement. Even if we ignore the evidence of Homeland bias against the diaspora, and assume that the U.S. government and public really would like to give us a fair shake, their own domestic concerns come first. And when it comes to Totalization Agreements, their major concern is not Social Security tax burdens on emigrants but Social Security payments to guest workers and immigrants. Senior citizens’ groups and immigration-restrictionist organisations voiced strident objections to the negotiated agreement with Mexico, and to avoid the political fallout, apparently the Bush administration never even bothered submitting the agreement to Congress.

Underestimates of effects on the diaspora

The Social Security Administration appears to have grossly underestimated the benefits of a Totalization Agreement to the diaspora in Mexico: in another press release, they claimed that it would affect only 3,000 U.S. citizens there. Like FinCEN’s FBAR estimates or the IRS’ old Form 8891 estimates, this figure is apparently based on the actual number of filers rather than a reasonable guess at the number of people who should be filing.

Given the State Department’s estimate of more than a million U.S. citizens in Mexico, the idea that only three thousand would benefit from a Totalization Agreement is not even remotely plausible. This is especially true given Mexico’s high self-employment rate: for example, in 2005, it had the fourth-highest self-employment rate of all OECD members, at more than a quarter of the non-agricultural labour force. (It would be a mistake to assume that nearly all Americans in Mexico are retirees and thus unaffected by Social Security taxes: many of them are the U.S. citizen spouses and children of former immigrants who have been deported, while others are just ordinary young and middle-aged people who wanted a fresh start.)

The connection to FATCA

Back in the mid-2000s, most self-employed U.S. citizens in Mexico probably weren’t filing U.S. taxes anyway, but a few years later Congress would pass FATCA in an effort to hunt them all down. Of course, FATCA wouldn’t have taken off if foreign governments had banded together to tell Washington to go fly a kite. Unfortunately, that never happened, partly because a number of major developing countries were holding out false hopes. They thought that a cooperative attitude towards FATCA’s violation of their sovereignty would earn them enough brownie points for Obama to go to bat for them in front of Congress to help them extract concessions from the U.S. in return.

In particular, some countries wanted a Totalization Agreement to benefit their guest workers — who go to the U.S. and pay into Social Security but return home with nothing to show for it. India in particular has been pushing for several years on this issue, and continues to do so today, to little effect. Apparently New Delhi signed its IGA in hopes that a Totalization Agreement would also be forthcoming. Sujeet Rajan of American Bazaar, among others, is struggling to disabuse the Indian government of its illusions; as he wrote in 2014:

The latest FATCA treaty just underlines – in red markers – how the US has been able to twist India’s arm where it really matters, without having to compromise anything in return. While US implements its rules and regulations with impunity, scores diplomatically on the world stage, India struggles to stay at par. Its stance is more about bravado and bluster than achieving concrete results.

For decades, the Indian community here has been crying hoarse over how NRIs who return back to India after working in the US never get back even a fraction of the Social Security and Medicare taxes they paid as residents. These substantial taxes are accrued from every paycheck or annually – as the cases may be – and is like gifting money to the US, if they are not availed of as Permanent Residents who go on to retire in this country or as Citizens who live to see the day of their pension checks.

The bruising which Bush faced over the Totalization Agreement with Mexico appears to have had a chilling effect on U.S. negotiations not only with developing countries but developed ones too: in the past 10 years, only five new agreements have come into effect, with Japan and four EU members, compared to eleven in the period 1985–1994. Only one agreement — the one with Slovakia — has come into effect in the past five years.

Hungary signed an agreement with the U.S. just a few weeks ago; hopefully, since they’re also an EU member state and don’t send that many immigrants to the U.S., that agreement will come into effect without any domestic political hiccups. However, the U.S. still has no Totalization Agreements with numerous high-income economies which have large American diaspora populations, including Israel, New Zealand, and Taiwan.

Meanwhile, in the rest of the world it’s by no means unusual for countries at sharply differing levels of economic development to sign totalisation agreements with each other — India for example has agreements with twelve countries including Canada, Japan, Finland, and Sweden, while China has agreements with Germany and South Korea. This reflects a global consensus that countries should cooperate to solve tax problems for workers who cross borders, rather than create problems like the U.S. does.

Conclusion

The effect of subjecting all citizens to the same tax system no matter where they live is that the livelihood of American emigrants is held hostage to domestic political uproars on issues with which they have little connection. Invariably, we end up being the eggs who get broken so the Homelanders can have their omelette. In this case it’s the Elephants’ fault. In numerous other cases it’s the Donkeys’ fault.

The concerns expressed by Homelanders over the domestic effects of Totalization Agreements with Mexico and other developing countries may or may not be valid — various Brockers no doubt have a wide variety of conflicting viewpoints on that question. But the simple fact remains: the U.S. is imposing punitive double taxation on emigrants to certain countries, and shows zero sign of being able to take any real action to solve the problem.

Just another reason to tell Uncle Sam to stick it. Also I believe in addition to the so-called ‘windfall provision,’ if you don’t earn a minimum income (which I believe is around $20,000), you pay into Social Security and don’t receive any credits (or quarters) for your taxes.

So if you’re on a low income you pay tax and receive absolutely nothing back in return not even a reduced SS pension.

Again Uncle Sam stick it.

Thank you, Eric, for your hard work in researching yet another aspect of the U.S.A.’s thoughtless and discriminatory tax practices. I will reference this post in my addenda to the UN Human Rights Complaint.

What’s the latest with Jim Jatras? I was following his website and comments and he seems to have gone quite about FATCA?

Here is recent Jim Jatras work in Sweden, Don: http://isaacbrocksociety.ca/2015/02/11/sweden-narcs-out-its-own-accidentals-to-usa/comment-page-1/#comment-5600634

@Calgary411 – Thanks – Already read the Swedish article, didn’t connect that one with Jim Jatras.

Isn’t it our fault for having left the US or for having an American parent?

@Eric, Thanks for the analysis, excellent as always. This is another reason why expanding the FEIE is not a real solution. Thankfully, Tom Coburn and Carl Levin are no longer in Congress.

@Eric

Thank you for posting this and for highlighting an issue that is misunderstood or ignored by many people. Pity the poor self employed dual NZ-US person in New Zealand who has just discovered his US “filing obligations” and needs to file 5 years of tax returns to renounce. These people may face bills of tens of thousands if they want to become “compliant” on top of the normal taxes paid to New Zealand. What a rort.

@Eric

Again, a very helpful analysis. I would hesitate a bit to call the U.S. citizens of Mexico an American diaspora. According to the Mexican government, the median age of U.S.-born residents is early teens and almost all of the U.S. born children in Mexico are living in households headed by Mexicans. Of course, they miss the Americans who are in Mexico illegally.

This is all too complex with too many agreements. There needs to be a simple law that removes the need for such agreements. I was thinking making contributions voluntary if you live abroad, yet if you select this then maybe for the rest of your life.

Should there now be separate agreements in regards to the Obamacare investment tax with all the individual countries? The countries could not figure this out as it is too complex.

In terms of population control, what’s the difference between the Americans and the communists from the 60s-80s?? Same tactics. Same rhetoric. Laws are used instead of walls.

Cross-commenting at this relevant post, JC’s:

http://isaacbrocksociety.ca/media-and-blog-articles-open-for-comments/comment-page-148/#comment-6018478

There is legal action by two US-French citizens for appeal of disallowance of credit of certain social security paid to France while they lived in France (now live in US).

Sounds like the usual caught by the definition of preventing double taxation in the Tax Treaty and Social Security Totalization agreement. None the less legal action!

@Calgary411 perhaps an IBS feature?

There is Disqus Comments allowed.

Appeal of Tax Court Decision Focuses on Foreign Tax Credit, Tests Scope of U.S.-France Totalization Agreement

http://www.globaltaxenforcement.com/tax-controversy/appeal-of-tax-court-decision-focuses-on-foreign-tax-credit-tests-scope-of-u-s-france-totalization-agreement/#more-2179