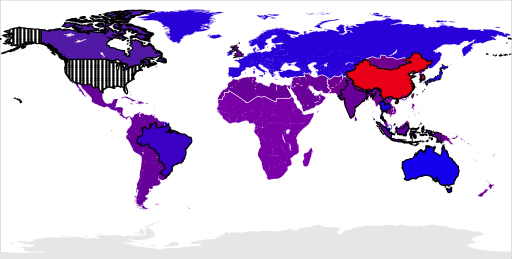

A simple data mash-up I’m surprised I’ve never seen before: number of high-net-worth individuals (HNWIs) vs. number of people who bought a U.S. green card through the EB-5 investor visa programme in the past five years, by country or region. The former number comes from Capgemini’s 2013 World Wealth Report (WWR), specifically the section on HNWI population estimates; the latter number comes from the State Department’s Report of the Visa Office, specifically Table VI, Part IV for each year.

| How many HNWIs in each country or region obtained EB-5 green cards in 2009–2013? | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

1 in 29 | ||

| 1 in 64 | |||

| 1 in 128 | |||

| 1 in 256 | |||

| 1 in 512 | |||

| 1 in 1,024 | |||

| 1 in 2,048 | |||

| 1 in 4,096 | |||

| 1 in 8,192 | |||

| 1 in 11,643 | |||

Note that except for certain countries, the WWR only provided estimates of HNWIs on a regional basis. The above map was thus coloured in by taking the total of EB-5s for the region and dividing it by the number of HNWIs; this means that some countries in the map are coloured in according to the average for the broader region, even though no one at all from that country got an EB-5 in the five-year period in question. Where the WWR did provide a country-specific estimate of the number of HNWIs, the country is outlined in black, except for Hong Kong and Singapore which are circled.

Table of contents

- The data

- Explanation of table

- Analysis

- Language issues

- Escaping obligations at home

- Does this post have anything to do with Americans abroad?

The data

| Region | HNWIs, 2009 | EB-5s, 2009–2013 | Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total HNWIs outside of U.S. |

7,157,100 | 21,230 | 337 |

| Excluding mainland China, Taiwan, and South Korea | 6,679,800 | 2,567 | 2,520 |

| Asia-Pacific | 3,022,500 | 6,874 | 157 |

| China | 477,300 | 16,575 | 29 |

| South Korea | 126,800 | 1,579 | 86 |

| Taiwan | 82,800 | 509 | 163 |

| India | 126,700 | 124 | 1,022 |

| Indonesia | 24,000 | 19 | 1,263 |

| Hong Kong | 76,000 | 54 | 1,407 |

| Thailand | 49,800 | 7 | 7,114 |

| Japan | 1,650,400 | 174 | 9,485 |

| Australia | 173,600 | 18 | 9,644 |

| Singapore | 81,500 | 7 | 11,643 |

| Rest of Asia-Pacific | 153,600 | 195 (47% Vietnam) |

788 |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 94,600 | 171 (82% Nigeria & South Africa) |

626 |

| Middle East | 373,600 | 418 (86% Iran & Egypt) |

957 |

| Latin America & Caribbean | 448,300 | 341 | 1,315 |

| Brazil | 131,100 | 45 | 3,260 |

| Other | 301,600 | 296 (76% Mexico & Venezuela) |

1,019 |

| Canada | 251,300 | 104 | 2,416 |

| Europe | 2,947,800 | 922 | 3,197 |

| United Kingdom | 448,100 | 469 | 955 |

| Other | 2,499,700 | 453 (37% Russia) |

5,518 |

Explanation of table

According to Capgemini, “HNWIs are defined as those having investable assets of US$1 million or more, excluding primary residence, collectibles, consumables, and consumer durables” — in other words, twice the EB-5 “Targeted Employment” investment threshold of US$500,000. (This definition also means that almost all of them would be “covered expatriates” if they moved to the U.S. on an EB-5 green card but then later changed their minds after seven years or after becoming citizens.)

Capgemini basically used World Bank regions in dividing the world: thus “Middle East” extends as far west as Morocco, while “Latin America” includes all the countries of the Caribbean which the UN Geoscheme would classify as “North America”. For Africa and the Middle East, Capgemini’s report did not provide any country breakdowns of the number of HNWIs.

For all other regions, the above table is divided into countries for which Capgemini’s report provided a country breakdown, and “Other”, consisting of the countries in that region for which Capgemini did not provide an individual breakdown of the number of HNWIs. (For example, under “Latin America”, “Other” consists of Argentina, Colombia, etc. — every country besides Brazil). The HNWI total for “Other” rows consists of the regional HNWI total minus the number of HNWIs in countries for which a breakdown was provided. Underneath the EB-5 total for “Other” rows, any country which contributed more than 10% of that total is listed.

Analysis

The stock account of why about three percent of Chinese HNWIs have bought EB-5s in the past five years goes something like this:

It is not hard to understand what may have pushed this group of Chinese away from their hometowns, given recent news about pollution, food safety, quality of life, education and infrastructure in China. Even the inconvenience of carrying a Chinese passport, which makes international travel a nuisance, can drive some people to seek passports of a more convenient color …

Ren Zhiqiang, a real estate tycoon hugely influential in China’s sphere of public opinion, may have pointed out the real psychological reasons behind the latest wave of emigration: “There are so many reasons for emigration, but the most important one is the sense of security. Safety in life, wealth, food, air, education, and rights. The lack of a sense of security is one of the important reasons why there is social instability. Only by giving citizens a sense of security can a stable society be established.”

Of course, these comments apply equally to Indonesia, India, and Thailand, which rank not much better than China on the Failed States Index and which have similar problems with food safety and air pollution, but where the proportion of HNWIs obtaining EB-5s is two orders of magnitude lower. Conversely, this standard account offers no explanation whatsoever of why far cleaner and richer Taiwan and South Korea have nearly as many of their HNWIs seeking U.S. green cards as China does.

Clearly, quality of life at home has some impact — no doubt why so few Australian and Western European HNWIs are interested in U.S. immigration. But there’s other factors at work.

Language issues

One obvious principle is that HNWIs of any nationality are not very interested in moving to a place where their mother tongue is not already widespread. They might see an objective improvement in their quality of life, the cleanliness of the air they eat and the food they breathe, or better chances for their children to learn accentless English and acquire globally prestigious university degrees. But that is for most overridden by the fact that they would be starting over as inarticulate foreigners of no particular social status, and — especially for Africans and Middle Easterners — might face racial prejudices in addition. Falling to the bottom of the pecking order in the U.S. is a bitter pill to swallow for someone who made it to the top at home.

Thus Thai and Indonesian HNWIs prefer Singapore over Southern California, Koreans & Iranians prefer Southern California over Singapore, many Taiwanese & mainland Chinese would be perfectly happy in either destination, while Arabs reject both destinations in favour of Dubai, and Russophones prefer Cyprus, London and Baltic countries. Similarly, Britons like John Cleese find that the low taxes of Monaco or Switzerland aren’t enough to make up for being surrounded by the French language all the time — and so instead they either stay in the U.K. (under “non-dom” status if they can swing it, or as ordinary tax residents otherwise), or they go for EB-5s to get admission to Anglophone America at a rate of 3x the average across the rest of Europe.

HNWIs who migrate may not wish to live 100% of their lives in an expat bubble speaking only their mother tongue, but after a difficult day, or when dealing with sensitive & complex legal or financial matters, they would certainly prefer dealing with service providers who speak their language. So we should not be surprised by the high rate of EB-5 utilisation in Sinophone countries, not to mention a sharp divide between Hispanophone Latin America & Lusophone Brazil, and between Anglophone Britain and the polyglot European continent. (The U.S. of course has deeply-rooted communities of Acadian & Quebec Francophone origin, but most of them no longer speak the language thanks to laws like Maine’s forbidding the use of French as a medium of instruction in schools — and the ones who still do speak French have mostly retired already and are unavailable to work as service providers for wealthy expats in Boston, let alone New York or California)

Escaping obligations at home

But the question remains — why do some countries which speak languages widespread in the U.S. have high EB-5 use rates, while others do not? Why does the U.S. get Sinophone Taiwanese and Anglophone British HNWIs, but not Singaporean nor Indian HNWIs? The most consistent explanation I can think of is that the U.S. is offering a haven for rich people and their children to avoid the societal duties imposed on them by their home countries, and the rate differs by how desirable such escape is and how likely a move to the U.S. is likely to protect them from whatever they’re trying to escape.

Of course, no matter how bad food safety & schools & societal obligations are in their countries, 99.9% of HNWIs find that it’s psychologically far less costly to take those “investor visa” funds and spend them at home buying imported organic vegetables & meat at upscale supermarkets and sending their kids to “international” school instead. So what societal obligations are we talking about, specifically?

Probably not. For HNWIs, there are far simpler ways to reduce individual tax burdens than by emigrating — that’s what tax lawyers and lobbyists are for. Furthermore, for an HNWI whose investments are mostly located in the country where they live, emigration might not change their tax burden by much anyway — the companies in which they invest will still face corporate profits taxes, and their dividends will probably face withholding at source. And almost any country you move to will figure out a way to get some money out of you, on VAT & property taxes if not on income & wealth taxes.

Second, at least for mainland Chinese and Taiwanese HNWIs who migrate, it seems that generally they’re not picking their destination based on the lowest tax rate, otherwise you’d see many more going to Hong Kong, Singapore, Malaysia, or some Caribbean and Latin American countries which have territorial tax systems. In reality, Hong Kong attracts only about half as many mainland Chinese investor visa applicants as the U.S. does, and Malaysia and Singapore (let alone the Caribbean and Latin America) are even less popular — more on that below.

One obvious societal obligation which is difficult to escape except by emigration is obligatory military service, which Taiwan had during the entire period to which the above map pertains (they are now struggling to abolish it and create an all-volunteer army), and which South Korea still retains with no end in sight thanks to the ongoing threat from their starving, nuclear-armed neighbours up north. The draft is unlike taxation in its extremely binary nature: you can argue with the tax collector all day about whether some payment you got constitutes “income”, but unless you plan to bribe a doctor or a guy in the records office it’s a lot harder to argue with the draft board that you (or your son) are an adult male in good health who hasn’t served yet.

This has two implications, First, because the draft is so clear-cut, the public understands it quite well, and it’s a lot harder for lobbyists to sneak a draft exemption for rich kids into the Military Service Act than it is to sneak a tax loophole for rich kids into the Revenue Act. And second, it is obvious whether or not you have complied: absent criminal prosecution, tax non-payment is not a matter of public record nor of casual conversation, but military service certainly is. However, both Taiwan and South Korea, unlike the U.S., are anxious to create reasonable exceptions from societal duties so that members of the diaspora are not penalised for retaining their connection to their country of birth — and so emigration remains an option for that minority of people who want to use their money to make sure their sons don’t have to serve. In some cases, the loopholes are even big enough to allow them to return to live in Taiwan or South Korea after acquiring their foreign status.

This would also explain why Hong Kong is not a popular investor-visa destination for Taiwanese emigrants — Taiwan’s draft exemption for people with permanent residence in foreign countries does not apply to Hong Kong after its reversion to Beijing’s control, because — for historical reasons — Hong Kong is not considered part of a “foreign country” under Taiwanese law, and so Taiwanese who establish residence in Hong Kong don’t get “emigrant status” (僑民身分). Furthermore, Hong Kong’s investor visa does not grant instant permanent residence anyway; it simply lets you stay in the city without a job or a sponsor until you’ve finished the seven years of ordinary residence required to apply for PR.

However, this still doesn’t explain the high EB-5 utilisation rate in mainland China, which does not have a draft.

Another sort of “obligation” which can be avoided by emigration is the obligation to do the time when you commit a crime. Obviously this doesn’t work for small-time pickpockets, pimps, and purveyors of proscribed pills, who will find themselves extradited back home to face the music almost as a matter of course. But for wealthy people whose money has a shady past, a move to another country can be quite helpful — as long as you think your new country will protect you.

This may explain why high EB-5 utilisation rates can often be found in countries which have rather tense relationships with the United States, like Iran or Russia: in the absence of an extradition treaty, HNWIs from those countries whose are suspected of having acquired their wealth by shady means — regardless of whether the suspicions are true or false — can probably beat any attempt to send them back home to face corruption charges by keeping their noses clean in the U.S. while claiming that the charges are politically motivated.

Even if there is an extradition treaty (like with Venezuela, another large source of EB-5 investors) and you’re facing well-substantiated, non-political charges, you can always find some credulous human rights group to take up your side of the argument and portray you as an innocent, oppressed businessman seeking Freedom & Democracy. (And if all else fails, you can just make a campaign contribution to Bob Menendez — thanks to The_Animal for posting the link in another comment thread).

Conversely, this might also explain why certain highly-corrupt countries nevertheless do not see many HNWIs getting EB-5s so they can enjoy “the protection of the United States”. Brazil, Thailand, and India each has an extradition treaty with the U.S. and a reasonably good public image, so fugitives from their justice systems are rather unlikely to be able to fight extradition by convincing a U.S. judge that the home country is trying to persecute them politically rather than just charge them with a crime. And it similarly explains why Hong Kong is not a more popular destination for mainland Chinese investor visa applicants, attracting only 16,807 in the last 10 years — aside from the higher price tag, the only mainland Chinese who can move to Hong Kong safely are the ones who are reasonably sure that Beijing will not come after them and demand an accounting of how they made their money, because Hong Kong will offer them no protection from such demands.

Does this post have anything to do with Americans abroad?

Defenders of the U.S.’ system of global citizenship-based taxation often try to claim that without that system, rich Americans would decamp en masse to Singapore along with Eduardo Saverin in order to escape “high taxes at home”. In reality, a grand total of a couple of dozen out of the Homeland’s four-million-odd HNWIs can even be bothered to inquire about applying for special tax incentives in Puerto Rico — where they don’t need a visa, and don’t even have to pay capital gains on a deemed disposal of their assets like under the expatriation tax, but can simply wait until all of their U.S. mainland stock appreciation becomes “Puerto Rico-source” by the magic of 26 CFR 1.937-2(f). People might choose a destination based on tax reasons when they are already predisposed to moving in the first place, but Homelanders are overwhelmingly predisposed against moving, and even more so against moving internationally.

It’s reasonable to assume that the rich, simply by dint of being well-travelled and knowing expert advisors and other sources of information, have access to better information than the middle-class or poor about the benefits & costs of migration. So simple revealed preference tells us that unlike Chinese & South Korean HNWIs, American HNWIs do not see international migration as their best strategy to preserve wealth while avoiding societal obligations, and that they are likely to be correct about that judgment. In contrast, they have spent their lives building up quite some social status & political connections, and quite often their best strategy is to stay right at home.

Those of us who do go abroad and renounce citizenship are drawn from the population who lack such connections, contrary to the stereotypes with which Congressional demagogues try to paint us.

It wouldn’t surprise me if the Chinese rich started to become less interested in the US as China changes from an exporter to more domestic consumption. Will the tables have turned with people in the US interested to going to China?

Once China sorts out their pollution problems and the RMB becomes a reserve currency, what will be really separating the two?

@Eric

Many of the British HNWIs may not necessarily be British. There are lots of foreign non-doms resident in London and I would imagine that these people are particularly footloose/rootless.

Britons are generally much more footloose, largely because of the empire, high cost of housing and the climate. In some industries, like film and computing, there is also the sense that the U.S. is where the action is. It is unfortunate that you used Cleese, since he is not the most obvious example and has been back in the U.K. now for over a year, even though he is reportedly under a great deal of financial pressure following an acrimonious divorce.

Isn’t the U.S. more of a tax haven for money rather than residents anyway?

@Publius: The State Department’s Table VI is by foreign state of chargeability rather than by consular post. So most of the ones under the “British” category should be actually born in the UK, though there is some fuzziness which allows for counting spouses of different nationalities under only one country or the other. So if some of the British HNWIs counted in Capgemini’s report are actually non-doms, then the real HNWI-to-EB5 ratio for UK natives would be lower.

(DHS does their green card tables by country of last permanent residence, but unfortunately they don’t break it down as far as individual green card categories, only by employment-based vs. family-based. FWIW, for example from 2004 to 2008 there were a total of 36,050 employment-based green cards granted to people born in the UK, and 40,190 granted to people whose country of last permanent residence was the UK.)

Look at this amazingly rosy view of what’s going to happen in Israel after FATCA:

http://blogs.timesofisrael.com/us-taxpayers-in-israel-listen-up/

It makes it seem like the IRS will just send you a letter asking why you didn’t report the money just like the case of forgetting income in the US! Amazing.

@Neill

Gee whiz… forgot to report the interest…. Here is the bill for it… what the f* Why the f* are they taking all of it? And why the f* do I owe more?

What kind of bs reporting is that? If u don’t understand….. read up on it… don’t just write a bs article

@US_Person_Foreigner

I hope the Times of Israel is some dinky thing. Otherwise this level of reporting should be an embarrassment.

@Neill

It is a “dinky” thing – it’s not a regular newspaper (at least not here in Israel). The blogger who wrote is a well known (and expensive) US tax accountant.

Pingback: The Isaac Brock Society | China makes officials pledge to bring home overseas family members & give up foreign permanent residence or citizenship

Well this is amusing: even Voice of America bloggers admit that a very large category of Chinese HNWIs most interested in U.S. immigration are not exactly entrepreneurs looking for better business opportunities:

http://www.voachinese.com/content/heqinglian-blog-20141105/2510159.html

And of course, if you’re a rich person who doesn’t have relatives in the U.S. or an employer to sponsor you, and your country doesn’t have a treaty of navigation & commerce with the U.S., guess how you move to the U.S.? EB-5, obviously …